A video recording of the synchronous sessions for the week will be uploaded after each class to this folder (https://www.dropbox.com/sh/zjuxktfzizh7pdf/AAC7dFC5cauIsRRk6ft8rSoIa?dl=0) (the password can be found on the “Welcome” page of this course’s Blackboard site – email me if you can’t find it)

Beginnings of the Animation Industry

This week we will look at some of the early innovators in animation, in Europe and in the USA. There is a strong relationship between early animators and print comics creators. We will discuss the impact of the first World War on the film industry and the development of the studio system. We will look at how distribution systems evolved and how the advent of sound film impacted the animation industry. We will also discuss the guidelines for the short paper that will be due on 10/26.

Jump to the different sections with the links below:

Émile Cohl / Winsor McCay / Comics and Early Animators / Effects of WW I on the Film Industry / Bray Productions and Cel animation / Fleischer Brothers / Distribution / Pat Sullivan and Felix the Cat / Advent of Sound / Stop motion developments / Assignment

Émile Cohl

Émile Cohl, born Émile Eugène Jean Louis Courtet, (1857-1938) was a French illustrator, caricaturist and animator. Early influences on his work include Guignol puppet theater and political cartooning. He worked with André Gill, a well known caricaturist from 1878 onward, first drawing the backgrounds to his illustrations. Gill’s style was influential on Cohl; large heads with small puppet bodies.

Cohl was active in artist and writers groups in Paris (the Hydropathes and L’Incoherents) that espoused “modern” ideas and styles. In 1907 Cohl was working at the Gaumont film studio, learning the techniques of filmmaking, and creating short animated sequences that were included in live action films. He created “Fantasmagorie” in 1908, it is considered the first completely animated film. It consists of over 700 drawings. The film is a series of transformations, with one character or object evolving into another character or scene. Cohl drew each drawing on a lightbox, photographed it (in twos), then traced the drawing with adjustments. He drew on white paper with a black line, and inverted the process in the final film. His work included his hands, a convention from the studio of J. Stuart Blackton that continued with later animators.

Cohl continued to make films with Gaumont through 1910. After leaving Gaumont, he worked for the French studios Pathé and Éclair. His work was widely distributed in the US and was extremely influential on the development American animators such as Winsor McCay. Cohl moved to Fort Lee, New Jersey in 1912, still working for the Éclair studio.. Fort Lee was a center of the early American studio system and Éclair was eager to break into the American market. He continued to work there until 1914 when he returned to France and continued to work for Éclair, releasing his last major work in 1920. His work was now considered old fashioned, eclipsed by films made in the American market. He died in poverty in 1938. (source- “Émile Cohl” Wikipedia)

Winsor McCay

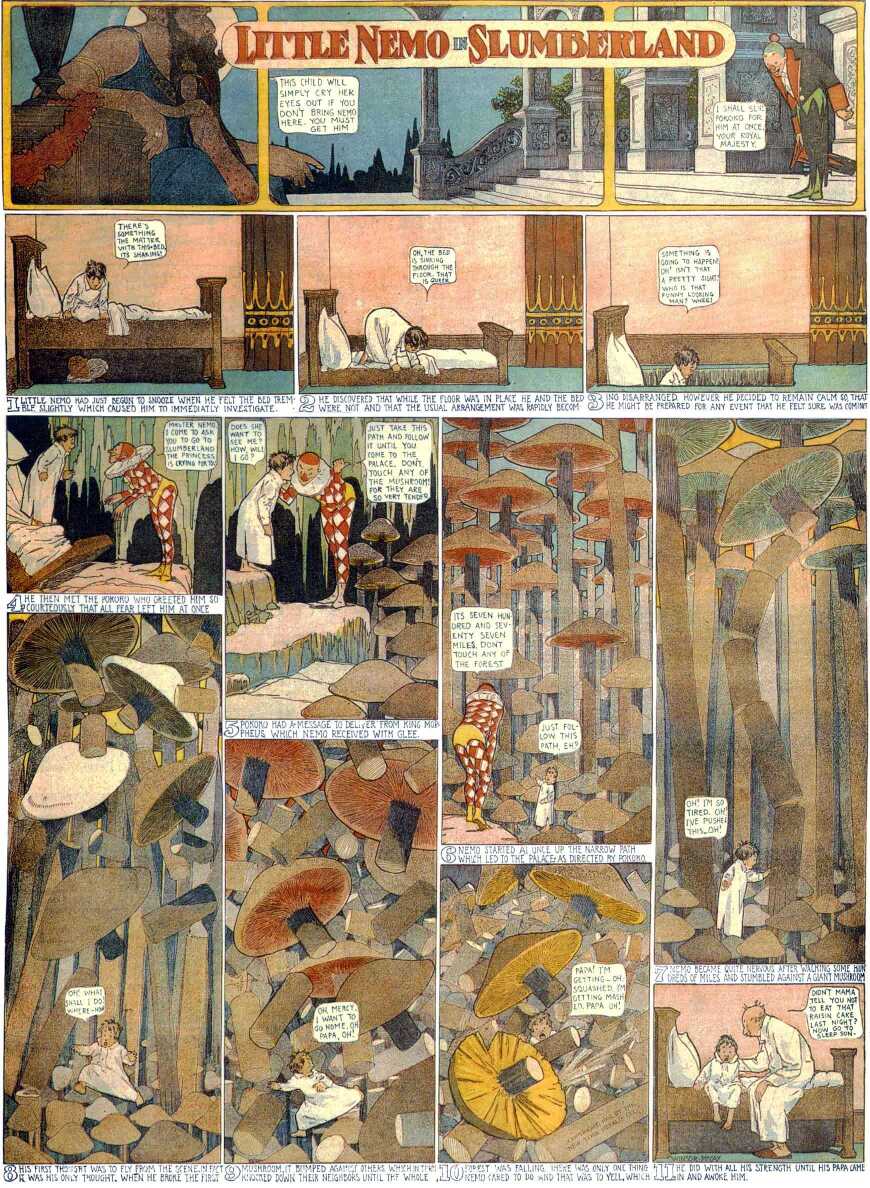

Winsor McCay (c. 1866–71 – 1934) was an American cartoonist and animator. He is one of many early animators who worked first in creating comic strips for newspapers before moving into film animation. After a start as an illustrator of posters and advertisements for dime museums, he began working for newspapers, first as an illustrator and occasional reporter. In 1903, he began writing and drawing comic strips which he continued to do through 1911. His most famous comic strip, Little Nemo in Slumberland, debuted in 1905 and continued in some form through 1924.

McCay was fascinated by the possibilities of animation and created an animation of “Little Nemo” in 1911. Live action sequences were added before and after the animation in this film. McCay toured with this film as a vaudeville act. McCay next worked on “How a Mosquito Operates” in 1912. He added this film to his touring act. “Gertie the Dinosaur” was next added to the act in 1914.

Gertie appeared to be responding to McCay’s commands on stage. These films had more complex backgrounds than the earlier McCay animations. McCay developed some techniques, such as using registration marks and identifying key positions, that later became standard in animation, though he never patented these techniques. McCay began working on “The Sinking of the Lusitania“, a recreation of the German torpedoing of a passenger ship, in 1916. It used cel animation and took 2 years to complete. McCay made several more films using cels, though some of them were not commercially distributed. McCay spent most of his later life working in cartoons rather than animation.

Comics and early animators

Starting in the 1890s, American newspapers printed cartoon strips, eventually in full color. Rival publishers William Randolph Hearst (New York Journal) and Joseph Pulitzer (New York World) regularly fought over artists and content. Many of the early animators in the United States had their roots in comic strips. We have already seen the importance of the work of Winsor McCay, but he was not alone in his involvement in both media.

The Katzenjammer Kids, created in 1897 by Rudolph Dirks, was published in a Sunday supplement of Hearst’s New York Journal. Many of the conventions of later comic strips, such as speed lines and speech balloons, were established in this work. A cartoon “Policy and Pie”, was created in 1918, directed by Gregory La Cava.

Another strip that was used as the basis for an animated series was George Herriman’s Krazy Kat which ran from 1913-1945 in Hearst’s New York Journal. A cat named Krazy is in love with a mouse named Ignatz. Ignatz does not return his affection, he hurls bricks at Krazy. Officer Bull Pup defends Krazy from Ignatz, and falls in love with Krazy. Krazy is sometimes referred to with female pronouns, sometimes male.

Krazy Kat was not popular with the general public, but was seen as surrealistic and poetic by intellectuals during the period when it was created, and it continues to have an avid following today. Here is an article on the gender fluidity of Krazy Kat by Gabrielle Bellot.

There were a number of animations based on the strip created by different studios: first Hearst’s International Film Service, then Bray Productions, followed by Winkler Pictures. Unlike McCay, Herriman did not do the animation.

The animation below, “Krazy Kat and Ignatz Mouse at the circus” was created in 1916 by the Hearst Vitagraph News Pictorial.

Effects of World War I on the film industry

We have seen that film production around the 1900s was dominated by studios in France. The devastation of World War I changed this. Film production as well as distribution was disrupted in Europe by the war.

“For French cinema, the war was a debacle. Before 1914, the Pathe and Gaumont companies had enjoyed commanding positions throughout the world. After the war, these two giants all but ceased production, and French cinema became (by and large) the work of small, quasi-artisanal companies, perpetually struggling to reach markets outside their borders.” (from Klawans, Stuart “FILM; How the First World War Changed Movies Forever” New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2000/11/19/movies/film-how-the-first-world-war-changed-movies-forever.html Retrieved June 2021)

The United States entered the war late and did not receive the same level of physical and economic destruction that Europe did. The US entered a period of post war economic prosperity. The film industry faded in France and gained prominence during this period first on the East Coast, in New York City and in New Jersey.

Bray Productions and the development of cel animation

John Randolph Bray (1879-1978) was an American cartoonist and animator who started a studio that developed techniques that changed the way that animated films were created. Bray worked as a cartoonist for the newspaper the Brooklyn Eagle when he first became aware of Winsor McCay’s animations. McCay’s work was created by drawing sequential drawings on paper, then filming them. Bray’s studio first developed a technique to print the background images of each drawing. Artists like McCay drew every detail of every single drawing, which was time consuming as well as more difficult to maintain consistency. Later on in the 1910s animator Earl Hurd (1880-1940) developed the process of using cels, or clear plastic sheets that could be layered on top of each other, with the action separated on layers and the background drawn on paper. This technique was eventually widely implemented across the industry. Earl Hurd created the series “Bobby Bumps”. Together Bray and Hurd formed a studio Bray-Hurd Process company, and they controlled the patent on cel animation from 1914-1932, when it went into public domain. Many other animators worked with Bray during the 1910s, including Paul Terry (creator of Mighty Mouse) and Max Fleischer.

Below is a short clip that explains the history of cel animation and how cel animation works.

Section 1:30 – 2:40 of the short documentary below about the Fleischer Studio (date unknown) explains the process of cel animation.

The Fleischer Brothers

Max Fleischer (1883-1972) and Dave Fleischer (1894-1979) were brothers who had an enormous influence on the early days of film animation. They founded a studio in New York City, Fleischer Studio (known also as Inkwell and Out of the Inkwell Studio) that was responsible for many of the technical innovations in animation as well as many of the characters that are still familiar to us today. The Fleischer brothers developed the technique of rotoscoping, and were also responsible for innovations in using sound. Max often acted as the producer, while Dave directed many of the animations. Characters they developed included Popeye and Betty Boop. Read more about them in Week 6.

Pat Sullivan and Felix the Cat

Pat Sullivan (1885-1933) was an Australian cartoonist who started an animation studio in New York City. One of the most well known characters that developed from that studio was Felix the Cat. Felix was created by American animator Otto Messmer in 1919. The first appearance of Felix was in “Paramount Screen Magazine”, though he was called a different name. Felix, a heavy drinker and a womanizer, was designed to appeal to adults. Sullivan controlled the rights to the character and was having difficulty finding distribution after “Paramount Screen Magazine” folded. Margaret Winkler, who was a secretary at Warner Brothers, decided to form a company and distribute Felix.

In the 20s, Felix was popular with the public; a plush toy of Felix was sold, and a comic developed recording his exploits. He was one of the first animated characters to achieve that kind of popularity. He became less favored in the 30s, when Sullivan did not adapt successfully to film with sound. Sullivan died of alcoholism in 1933.

Distribution

Much of the distribution of films during this period was controlled by the big studios such as United Artists and Paramount. They contracted with animation studios for content. If an animation studio was not able to contract with one of the big studios, they were able to sell a print to an agent and have distributed on a state’s right basis. The large Hollywood studios had a practice called block booking where studios signed theaters to contracts in which the theaters had to show the entire year of the studio’s output. This made distribution for international productions extremely difficult. This method was eventually struck down by the Supreme Court in 1948.

Margaret Winkler

Because of the difficulties of distribution, Margaret Winkler (1895-1990), a secretary at Warner Bros, saw an opportunity to distribute animated films. With the encouragement of Harry Warner, one of the founders of Warner Bros, she started a distribution company to distribute the work of the Fleischer Bros and other animated films. Her company eventually became a production studio as well.

“As the leading distributor of animated cartoons in the 1920s, Margaret J. Winkler played a pivotal role in the professionalization of the animation industry. Her company, M. J. Winkler, distributed and financed several of the most significant animated series of the period, including Pat Sullivan and Otto Messmer’s Felix the Cat, the Fleischer brothers’ Out of the Inkwell, and Disney’s Alice Comedies. (“Disney” here and throughout refers to the Disney Brothers Studio. Walt Disney as an individual will be referred to by first and last name.) Winkler’s management of these series shaped their development in both economic and aesthetic terms. Unfortunately, after her marriage to Charles Mintz at the end of 1923, her involvement in the business declined, and by 1926 she had retired from the film industry following the birth of their two children.” (from Cook, Malcolm “Margaret J. Winkler” https://wfpp.columbia.edu/pioneer/margaret-j-winkler/)

“Both Winkler’s importance as a female pioneer and her responsibility for the commercial success of Felix were sometimes acknowledged in the trade press. In 1924, Film Daily stated “few know Sullivan but there is hardly anyone who doesn’t know Margaret J. Winkler, the only woman distributor of short subjects in the business…her success has been most unusual” (“The Felix Vogue”). Additionally, Winkler was the only female businessperson included in a list of “Prominent Film Folk” attending a Chicago convention in 1923, alongside figures such as Marcus Loew and Lewis J. Selznick (“Prominent Film Folk”).

Winkler’s reputation made her a leading figure in the nascent animation industry she was helping to build and a natural contact for animation studios looking for financing and distribution. It is important to note that roles and titles within the animation industry were at an embryonic stage at this time and distinctions between “distributor” and “producer” were fluid and do not necessarily reflect our present day understanding of these positions. Winkler was consistently referred to in the trade press as a distributor; however, this does not fully communicate the central role she had in instituting production and underwriting the financial expenditure of production, responsibilities more typically associated with a producer. There is good evidence that Walt Disney would not have been able to make the Alice films if he did not have a contract with Winkler, as it guaranteed a financial return.” (from Cook, Malcom “Margaret J. Winker”)

Advent of Sound

Before sound was integrated into film, there were often musical accompaniments to silent films, and sometimes sound effects. In Japan, actors called benshi narrated films. Throughout the 20s and 30s, film studios in the US and internationally were working on developing synchronized sound for cinema.

There were a number of competing systems in the early days of developing synchronized sound. In 1920, American inventor Lee DeForest patented a sound on film process called DeForest Phonofilm. He worked with Max Fleischer, creating a distribution company. In Germany, a system was developed called the Tri-Ergon system. Pat Powers’ studio developed a technology similar to DeForest’s; Powers Cinephone. RCA Photophone was another early system. There were court cases over patent rights.

During this period, Warner Brothers and Fox Studios pursued different versions of sound technologies. Fox was developing sound on film, Warner Bros. worked on a sound on disc system called Vitaphone.

The Fleischer Bros. produced a series of cartoons with sound Song Car-Tunes between 1924 and 1927. Some of them used the Phonofilm process.

Paul Terry directed Dinner Time in 1928, with synchronized sound.

Steamboat Willie (1928) was produced by Disney and animated by Ub Iwerks. It integrated synced sound and and showed some of the possibilities of personality animation in the character of Mickey Mouse.

“When you walk down Disney World’s Main Street, the seven-minute long 1928 Mickey Mouse film STEAMBOAT WILLIE is likely to be playing. STEAMBOAT WILLIE was not the first animated sound film, as is often claimed. It was not even the first Mickey Mouse film. But STEAMBOAT WILLIE was the first widely released film featuring the iconic mouse, and it immediately captured audiences’ imaginations when it premiered before the now-forgotten feature film GANG WAR. The rest, as they say, is history. Mickey Mouse became the foundation on which the Disney Company was built, and today, the movie plays on a perpetual loop in Disney theme parks, cruise ships, and hotels as a reminder of the company’s humble beginnings and as a link to its creator and namesake, Walt Disney.” (from Decherney, P. (2019). Steamboat Willie. In C. Op den Kamp & D. Hunter (Eds.), A History of Intellectual Property in 50 Objects (pp. 168-175). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108325806.021)

Read more about Steamboat Willie and Mickey Mouse in Week 5.

Stop Motion developments

While hand drawn 2D animation was the dominant form, particularly in the United States, there continued to be developments in stop motion animation during this period, in the US and internationally.

In the US, Willis O’Brien (1886-1962) animated The Dinosaur and the Missing Link in 1915.. Thomas Edison hired him to do a series of pre-historic themed animations using clay and stop motion techniques.

In a later project, The Lost World (1925) directed by Harry O. Hoyt, O’Brien used similar techniques in the first feature film to use stop motion special effects.

“Based on a novel by Sherlock Holmes creator Arthur Conan Doyle, World was the first feature film to use stop-motion animation special effects by pioneer Willis O’Brien, who went on to work on Kong. He was able to combine miniature rubber-composite dinosaurs with live-action footage of humans by using a split screen.

On World, O’Brien created about five seconds of footage a day. The technology was so revolutionary that when Doyle showed an early test reel to the Society of American Magicians in 1922, The New York Times couldn’t decide whether “these pictures were intended by the famous author as a joke on the magicians or are genuine pictures.” (from Higgins, Bill “Hollywood Flashback: ‘Lost World’ First Brought Dinosaurs to Life in 1925” Hollywood Reporter https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/how-lost-world-brought-dinosaurs-life-1925-hollywood-flashback-1121367/ Retrieved June 2021)

To Demonstrate how Spiders Fly (1909) was created using stop motion techniques by British naturalist F. Percy Smith (1880-1945). Smith used stop motion techniques in films to demonstrate processes in nature.

In Australia, cartoonist Harry Julius did a series of cartoons that used cut-outs as well as some drawing in techniques reminiscent of J. Stuart Blackton titled Cartoons of the Moment. The War Zoo was created in 1915. A number of animators in the United Kingdom worked with hinged cut-outs, including artist and filmmaker Lancelot Speed (1860-1931).

ASSIGNMENT: Review for Quiz 1 + Journal entry

- Quiz 1 will consist of 10 multiple choice questions taken on Blackboard. You will have 25 minutes to complete it once you start. Please review all films and concepts covered during weeks 1 – 3.

- Respond to the journal entry prompt(s) on this page.