A video recording of the synchronous sessions for the week will be uploaded after each class to this folder (https://www.dropbox.com/sh/zjuxktfzizh7pdf/AAC7dFC5cauIsRRk6ft8rSoIa?dl=0) (the password can be found on the “Welcome” page of this course’s Blackboard site – email me if you can’t find it)

Fleischer Studio, Warner Bros & MGM

While Disney came to dominate the American market for animation, several other studios were very successful in the first half of the 20th century, creating memorable characters still beloved today, and developing their own recognizable style.

Jump to the different sections with the links below:

The Fleischer Studio | Warner Bros. Cartoons | Metro Goldwyn Meyer (MGM) | Assignment

The Fleischer Studios

Rotoscope and other patents

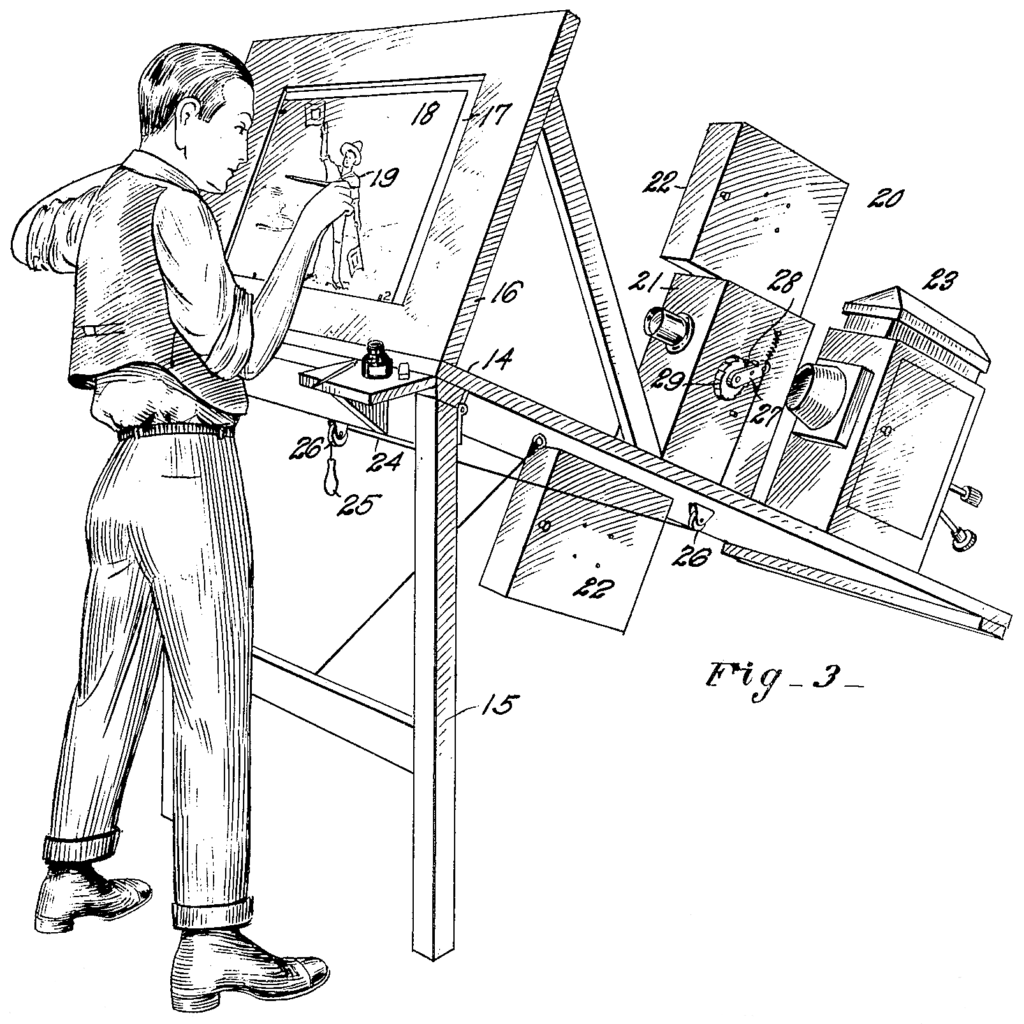

The history of the Fleischer Studio is tied to an important animation technique still used in some productions today: rotoscoping. “The seeds for what would eventually become Fleischer Studios were planted in 1915 when Max Fleischer, who was then Art Editor for Popular Science Magazine, invented the rotoscope. Max was fascinated by early attempts at animation and felt certain he could improve on the jerky movement he saw on screen. The rotoscope enabled animators to draw figures, frame by frame, over filmed action, thereby creating more life-like movement. The first rotoscoped film took over a year to make, and lasted only about a minute, but the results were so startlingly smooth and life-like that animated cartoons were forever altered.” (from flesicherstudio.org). The legacy of rotoscoping is a complicated one: Although it allowed for much smoother motion than those found in the early animations of the 1910s (see week 2), the ultra-realistic nature of the movement applied to stylized cartoon characters tends to give the animation an “uncanny” quality (at the awkward border between realism and exaggeration). While Walt Disney used the technique in “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” and a few subsequent animated films, a lot of his animators weren’t fond of the technique and regarded it as a “crutch”. Over the years artists and directors have used the technique’s uncanny quality very thoughtfully. For example, Richard Linklater’s “Waking Life”(2001) uses rotoscoping to echo the “dreamlike” structure and narration of the film.

This short documentary (5 min) by Vox provides a good overview of the origins of the Fleischers’ rotoscope (and some of their other patents):

Early years

“J.R. Bray, a pioneer of early animation (see week 3), was intrigued by Max’s early rotoscope work, featuring his brother Dave Fleischer in a clown suit, and hired Max with the idea of producing a series of Koko films to be released under the title “Out of the Inkwell.” But with the outbreak of World War I, Bray instead sent Max and fellow Bray staffer Jack Leventhal, a brilliant mechanical draftsman, to Ft. Sill, Oklahoma where they made some of the first training films ever made for the US Army, and the clown films were temporarily put on hold. Upon returning to New York, Max worked on a number of Bray projects including some of the very early theatrical Koko films.

In 1921 Max left Bray Studios and, together with his brother Dave, launched a new company: “Out of the Inkwell, Inc.” They hired one employee, Charlie Shettler, who stayed with the studio until it closed twenty years later. Out of the Inkwell’s first “studio” was a New York City basement apartment; the brothers even shot some of the live action sequences for these early films in their own living rooms. But demand for the Fleischers’ cartoons quickly grew. By 1923 they had a staff of 19 and the studio was able to move into what would become its longest lasting location: 1600 Broadway in the heart of New York City.” (from flesicherstudio.org) At its peak, it was the largest animation studio in NYC (with around 250 staff members). While they worked with Margaret Winkler (see week 3) to distribute their shorts early on, they set up their own distribution company in 1923. The studio was very much a family-run operation. Not two, but five of the Fleischer brothers worked there: Max was head of the studio/producer, Dave was credited as the Director, Charlie was chief engineer, Lou was in charge of music, and Joe was head of the electrical department.

Similarly to what happened at the Disney Studio (see week 5) a lot of experienced animators who worked at Fleischer Studios through the 1920s moved to other companies around 1930, leading to new hires and dynamics. Lillian Friedman was hired in 1931 as an in-betweener, but she was promoted to animator shortly after that, becoming the first female animator in the American Studio System. Her talent obviously had a lot to do with this, but the Fleischers weren’t really early feminists: they saw an opportunity to exploit her talent because she was a woman. She was paid $40/week compared to $125/week for men in her position.

Style

In contrast to Disney who focused on the development of linear and emotionally complex narratives starting in the 1930s, at Fleischer, narrative timing was much more fluid. Their shorts were focused on single scenes and the gags within it. Dave Fleischer also disliked still images and animators were instructed to have characters and even backgrounds moving/bouncing rhythmically at all times. Fleischer films were popular worldwide due to their adult-oriented plot elements, creative sound, and technological inventiveness. For example, the “Song CarTunes” series (mid-1920s) encourages audience participation (see “Ko-Ko Song Car-Tune: Tramp, Tramp, Tramp” (1924) (2 min) here).

Famous characters

Some of animation’s most famous characters came from the Fleischer Studios:

Betty Boop first appeared in a short in 1931 and had her own series from 1931 to 1939. She is unique in that era of American animation because of her sexualized persona – so much so, that her short skirt and suggestive movement had to be toned down because of censorship in 1934. “Snow White”(1933) (7 min) (see below) is probably the best-known Betty Boop film. It illustrates the Fleischer aesthetics (constant gags and movement, relatively little concern for linear narrative, improvised dialogue, rotoscoped imagery etc.). Although it is often thought that the primary influence for Betty Boop’s design was Helen Kane, a famous American white singer in the late 20s (one of her most famous songs includes Betty’s signature phrase “boop boop a doop”), Kane herself modeled her look and voice on Esther Jones, a famous Black singer at the Cotton Club in the 1920s. “The Forgotten Black Woman Behind Betty Boop” by Gabrielle Bellot (2017) dives into Betty Boop’s contested origin.

Popeye was first introduced as an animated character in a Betty Boop film in 1933. One year later he got his own series which lasted for more than 20 years. But his character was well known before the Fleischer took him on: he first appeared in Elzie Segar’s “Thimble Theatre” comics series in 1929 (and soon became the series most popular character). “In 1932, King Features (“Thimble Theater’s” publisher) signed an agreement with Fleischer Studios to have Popeye and the other “Thimble Theatre” characters begin appearing in a series of animated cartoons. Thanks to the animated-short series, Popeye became even more of a sensation than he had been in comic strips, and by 1938, polls showed that the sailor was Hollywood’s most popular cartoon character.” (from Wikipedia). “Popeye the Sailor Meets Sindbad” (1936) (16 min) (see below) was the first in a series of three Popeye Color Specials. It was nominated for the 1936 Academy Award for “Best Short Subject: Cartoons”, but lost to Walt Disney’s Silly Symphony “The Country Cousin”.

Relocation and full-feature films

In 1938, The Fleischers relocated to Miami, Florida (in part for lower taxes). This is where the studio’s first feature film (whose preproduction was started in New York) was completed: “Gulliver’s Travels” (1939) (1 h 16 min) (see below) (based on the book of the same name) was put into production after Disney’s success with “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” (1937). The film has some aesthetic similarities to the Disney film: it features dwarfs, a prince and princess, cute forest animals, has less of the constant movement and rubber-hose style animation still typical of Fleischer films, and is closer to a linear narrative than their other productions. Rotoscoping was used for a large portion of the animation and resulted in the character of Gulliver appearing stiff and unappealing. The film’s timing and character development is also underwhelming. “However, “Gulliver’s Travels” was a success at the box-office, earning $3.27 million in the United States during its original run. This box-office success prompted a second feature to be ordered for a Christmas 1941 release “Mr. Bug Goes to Town” (which was to be the studio’s last attempt at full-feature filmmaking). In spite of the profits earned domestically and internationally, Paramount held Fleischer Studios to a $350,000 penalty for going over budget. This was the beginning of the financial difficulties Fleischer Studios encountered as it entered the 1940s.” (from Wikipedia)

Downfall

“The studio was in need of new products going into the new decade, but the new shorts series that debuted in 1939 and 1940 (“Gabby”, “Stone Age Cartoons”, and “Animated Antics”) were unsuccessful. Paramount acquired the rights to comic book superhero Superman in 1941, and the Fleischers were assigned to work on a series of animated Superman shorts. The first entry, “Superman”, had a budget of $50,000, the highest ever for a Fleischer theatrical short, and was nominated for an Academy Award. The animated “Superman” series, with its action-adventure and science fiction fantasy content, was a huge success, but it was not enough to get the studio out of its financial trouble. While profits dwindled, Paramount continued to advance money to Fleischer Studios to continue the production of cartoons with its focus mainly on “Popeye”, “Superman”, and “Mr. Bug Goes to Town”. The Fleischers remained in control of production until November 1941. “Mr. Bug Goes to Town”, intended for release in December 1941, was not released until February 1942, and never recouped its costs. In spite of living up to his contractual obligations and delivering the film, Max Fleischer was asked to resign. Dave Fleischer had resigned the month before, and Paramount finished out the last five months of the Fleischer contract without the Fleischer brothers. The last cartoon produced at credited to Fleischer Studios was the Superman cartoon “Terror on the Midway”. Paramount formed a new company, Famous Studios, as a successor to Fleischer Studios and relocated back to the original 1600 Broadway location. Max and Dave Fleischer were left to find jobs at other studios. Today Fleischer Studios continues to hold the rights to Betty Boop and associated characters such as Koko the Clown, Bimbo and Grampy. It is headed by Max’s grandson Mark Fleischer, who oversees merchandising activities. (from Wikipedia)

Warner Bros. Cartoons

Beginnings

Warner Bros Studios had been in Hollywood for a number of years before it began to distribute animation. It was established and run by four brothers from Ohio who started in distribution in 1905 and expanded into producing live-action films by the mid-1910s. By the late 1920s, it had become one of the the “Big Five” studios in Hollywood, thanks largely to its early adoption of sound (the studio released “the Jazz Singer”(1927) – the first synch-sound film).

The studio ventured into animation in the early 1930s, led by Leon Schlesinger (see week 3). One of the studio’s first character was Bosko – a black character designed and animated by Hugh Harman and Rudy Ising – two white men, which displayed an array of African American racist stereotypes (read more about this in “The Bosko and Honey Revision: Warner Brothers’ Attempt to Hide Sexism and Racism” (2010) by Anderson Evans).

In 1933, when Harman and Ising left for MGM, Leon Schlesinger opened a studio in his name (which he later sold to WB and became the Warner Bros. Cartoons studio) for which he hired a lot of new talent that would play a big role in the creation of some of animation’s history most popular characters and series: Porky Pig (1935), Daffy Duck (1937), Bugs Bunny (1940). These characters and those that followed (i.e: Wile E. Coyote, Road Runner, Tweety & Sylvester etc.) were featured in short films (primarily the “Looney Tunes” and “Merrie Melodies” series) that specialized in very stylized and over-the-top physical comedy, and inventive use of sound.

Sound

Sound also became a huge part of the studio’s style of humor. The emphasis they put on scoring, sound effects, and dialogue was unique at the time. For a number of years the music department was led by Carl Stalling (1891-1972) (who used to work at Disney, and joined WB in 1936 where he stayed until he retired). On average, “Stalling composed one score every week for 22 years. Stalling had full access to the expansive Warner Bros. catalog and musicians. He could also use the fifty-piece orchestra of the company. The executives at Warner Bros. in fact insisted that Stalling should use as much music and songs from their feature films as possible. Their dual goal was to help promote the animated shorts by associating them with already popular music, and to help promote the songs themselves by giving them additional publicity. Stalling is among the first music directors to extensively use the metronome to time film scores. His stock-in-trade was the “musical pun”, where he used references to popular songs, or even classical pieces, to add a dimension of humor to the action on the screen. Working with directors Tex Avery, Bob Clampett, Friz Freleng, Robert McKimson and Chuck Jones , he developed the Looney Tunes style of very rapid and tightly coordinated musical cues, punctuated with both instrumental and recorded sound effects, and occasionally reaching into full blown musical fantasies. Stalling’s working process involved meeting each animated short film’s director or directors before the animation process begun. Together they set the time signatures to which the short was to be drawn. The animators of the film were measuring animation frames per beat. After the animation process was completed, Stalling would receive the animators’ exposure sheets or bar sheets. The sheets broke the animation, dialogue, and sound effects into musical bars, which Stalling would then use to create his score for the film.” (from Wikipedia).

Treg Brown (1899-1984), a trained musician, and sound effects editor, started working on Warner Bros. animated films in 1940 and developed unique sound effects using cowbells, jet engines, skidding car tires etc. from the studio’s live action sound library as well as sounds he recorded himself. The short documentary below (11 min) gives a a good overview of Brown’s inventiveness:

Mel Blanc (1908-1989) lent his voice to many Warner Bros. characters. He started in radio in 1920s, and came to be known as “the man of a thousand voices”. Watch the short documentary below (3 min) for a sample of Blanc’s work:

Directors

In contrast to the Disney and Fleischer Studios where the studio founders/owners made most of the creative decisions, directors at Warner Bros. were given a fair amount of freedom in expressing their individual comic sensibilities and aesthetic.

Bob Clampett‘s (1913-1984) first job at 18 was as an in-betweener at Warner Bros in 1931. He was quickly promoted to principal animator for Tex Avery (see MGM section below) in 1935 (while Chuck Jones – see below – took his role as in-betweener). He was then given the title of director in 1936 and remained in that position until 1946. He created some of the most beloved films in animation history. Much of his output involved the character of Porky Pig. “The Great Piggy Bank Robbery” (1946) (see excerpt (3 min) below): is a great example of Clampett’s style: rapid timing, total disregard for physical reality, exaggerated poses, and references to popular culture (in this case Dick Tracy, an American comic strip police detective).

Chuck Jones (1912-2002) worked in the same unit as Clampett but eventually developed his own unique sensibility. He was trained at the Chouinard Art Institute, and was part of the first generation of animators to have formal animation training. He started his career at Ub Iwerks’ studio as a cel washer (whose role was to clean paint completely off the cels when a production was finished so the sheet could be reused. At the time, studios saw the plastic as more valuable than preservation). He joined Warner Bros in 1933 and stayed until 1963. He started directing in 1938, and became especially well-known for films featuring Bugs Bunny and Wile E.Coyote/Road Runner. Two of his closest collaborators were writer Michael Maltese (1908-1981) and layout artist/background designer Maurice Noble (1911 -2001) (Noble’s work is noteworthy. This short episode from the 99% invisible podcast is an interesting introduction. You can also learn about and see a lot more of his work in “The Noble Approach: Maurice Noble and the Zen of Animation Design” by Tod Polson (published in 2013). He also had a passion for classical music, and was interested in how music and sound could be used creatively in animation. For example, “What’s Opera Doc” (1957) (7 min) (see below) (story by Maltese; backgrounds by Noble), juxtaposes Richard Wagner’s imposing classical score with funny voices of characters and wacky persona. His interest in Modern Art also guided his minimalist/highly stylized approach to backgrounds (a perfect fit with Noble’s style) and relatively restrained movements that allows viewer to appreciate strong design elements.

1960s to today

The popularity of television led to the studio’s closure for several years between 1962 and 1969. “Warner reestablished its animation division in 1980 to produce Looney Tunes–related works. In recent years, Warner Bros. Animation has focused primarily on producing television and direct-to-video animation featuring characters created by other properties owned by Warner Bros., including DC Comics, the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer cartoon studio (through Turner Entertainment Co.) and Hanna-Barbera Productions.” (from Wikipedia)

Metro Goldwyn Meyer (MGM)

Beginnings

MGM was perhaps the grandest of the “Big Five” live-action studios during Hollywood’s Golden Age in the 1930s and 40s. They were known for lavish live-action features such as “The Wizard of Oz” (1939) and “Gone with the Wind” (1939) and for contracting a range of top actors.

The studio started distributing animation in 1930 with the “Flip the Frog” series which was created and animated by Ub Iwerks when he left Disney (see week 5). MGM distributed the series until 1933, after which they hired Harman and Ising who still owned their Bosko character (see Warner Bros. section above).

In the late 1930s MGM rethought its animation strategy. They offered a contract to Oskar Fischinger (see week 4) who created the Modernist short “An Optical Poem” (1937) for them. They also set up their own studio headed by the producer Fred Quimby who had been in charge of live-action shorts units. Finally, they hired staff members from Harman & Ising’s studio, including Bill Hanna (1910-2001) & Joseph Barbera (1911 – 2006) who would make huge contributions to the studio’s TV legacy (see week 10). They hired Tex Avery who had previously worked at Warner Bros (see above) in 1941.

Although Hanna & Barbera and Tex Avery were at MGM at the same time, their sensibilities were very different and there was little interaction between the 2 units.

Tom & Jerry (Hanna & Barbera)

In 1940, the studio’s most successful series, “Tom & Jerry” was introduced with a film called “Puss Gets Boots” (see below) directed by Hanna & Barbera. More than 100 Tom & Jerry shorts would be released by MGM up until 1957. The MGM composer Scott Bradley (1891–1977) provided scores for the series and almost all the other animated shorts made during his tenure at MGM (which ended in 1957). Unlike some his peers, he thought highly of cartoon music and considered it an art form with largely untapped potential. The recurring character of “Mammy” Two-Shoes – a racist archetype of a black woman shown mostly as a pair of legs – has “often been edited out, dubbed, or re-animated in later television showings. Her creation points to the ubiquity of the “mammy” stereotype in American popular culture at the time, and the character was removed from the series after 1953 due to protests from the NAACP.” (from Wikipedia)

In the video below (3 min) Whoopi Goldberg offers an introduction and analysis of Mammy’s role in the Tom & Jerry series:

Tex Avery (1908 – 1980)

While Tex Avery started at Warner Bros (see above), and his influence can be felt in Clampett’s work, he did his best known work after he joined MGM in 1942. “At MGM Avery’s comedy became more outrageous. Emotions were exaggerated by having characters’ eyes jump out of their sockets, jaws crash to the floor and tongues roll out to enormous lengths.(…) Avery’s influence on 1940s and 1950s cartoons is particularly clear when one looks at his rivals. Hanna & Barbera accelerated the tempo of their ‘Tom & Jerry’ series, adding more absurd gags and painful violence.” His films feature highly stylized images, dynamic storytelling, an adult sensibility, and an irreverent look at contemporary culture. “Red Hot Riding Hood” (1943) (7 min) (see below) showcases the talents of the animator Preston Blair (1908-1955), one of animation’s most renowned animator ,who would become a regular collaborator of Avery’s, shortly after his departure from Disney. “The cartoon gained a cult following and was particularly popular with Allied soldiers overseas, who could all see the comedy in a man (or wolf) starving for sex. Naturally Avery made several sequels starring the Wolf and Red.”. The short’s original ending – wherein grandma and the wolf are married and have children – was changed likely because of censorship that saw it as an allusion to bestiality.

Avery’s other memorable characters include Droopy and Screwy Squirrel.

Avery took a year’s sabbatical from MGM beginning in 1950 (to recover from overwork). His unit never recovered and was disbanded in 1953. Avery worked for the Walter Lantz studio for a few years. “When Avery left Lantz in 1955 he was completely disillusioned. He left the animation industry altogether and up until 1979 he primarily worked in TV advertising. He created ads and characters for the insect spray Raid and potato chips brand Frito-Lay. He also contributed to TV commercials starring Bugs Bunny and friends.” (quoted content in this section from Lambiek.net)

ASSIGNMENT: Short paper revisions

Work on your short paper. Take into account the feedback you received on your draft. Make sure to review the guidelines and grading rubric here as you work.