New audiences, early CGI experiments and gaming

This week we will cover some of the experiments with film and animation techniques that occurred during the 60s and 70s. During this period there were some early experiments with CGI. We will also look at the development of youth culture during this period and feature films designed to appeal to that audience. Additionally, we will look at developments in gaming.

Jump to the different sections with the links below:

Postwar formal experimentation /Early CGI experiments / Overview of 1960s and 70s youth movement / Animated feature films for the youth audience / From arcade games to personal consoles / Types of games / Online gaming / Indie games / Issues in gaming?/ Assignment

Postwar formal experimentation

In the period following WWII, there was new energy in avant-garde filmmaking, including animation. Some of the experimentation involved working directly on film, abstract imagery, and collage. In the 50s and 60s, artists began experimenting with technology and using computers to create animation.

Harry Smith (1923-1991) was an American artist, filmmaker, writer, collector and mystic. He was influenced by the writings of Allen Ginsburg, Jack Kerouac and other writers identified with Beat Culture, which was characterized by sexual liberation, drug use, spirituality, an interest in Jazz and other American forms of music. Smith is known for his animated films, as well as his six album compilation Anthology of American Folk Music. Smith’s animation involved collage, and direct manipulation of film, sometimes painting on the film. He moved to New York in 1950, where many of his animated films were made and where he continued to be a leading figure in Beat Culture. He frequently re-cut his films, which are often identified by numbers.

Here’s a quote from his description of his work from the catalogue of the Filmmaker’s Cooperative.

“My cinematic excreta is of four varieties: batiked abstractions made directly on film between 1939 and 1946; optically printed non-objective studies composed around 1950; semi-realistic animated collages made as part of my alchemical labors of 1957 to 1962; and chronologically superimposed photographs of actualities formed since the latter year. All these works have been organized in specific patterns derived from the interlocking beats of the respiration, the heart and the EEG Alpha component and should be observed together in order, or not at all, for they are valuable works, works that will live forever—they made me gray.” (from Sitney, P. Adams. “Animating the Absolute” Art Forum https://www.artforum.com/print/197205/animating-the-absolute-harry-smith-36216 Retrieved June 2021)

Smiths’s No.. 11 Mirror Animations (1956-1957) was shot in 16mm, using collage..

Like Smith, American filmmaker Larry Jordan (1934) worked with collage and his work shows the influence of European surrealism and Dada. In addition to creating his own films, he worked with visual artist Joseph Cornell on animations.

“Over his long career Jordan has essayed a number of strategies by which an avant-garde filmmaker might survive via his work. With Stan Brakhage he made a naive attempt to travel around America and earn a living by showing their first works from town to town. After an initial screening, to which not one person came, they gave up. But Jordan was undaunted: He founded two important showcases in San Francisco and was among the original organizers of the Canyon Cinema Cooperative, which still distributes avant-garde films after nearly fifty years in operation. He drew up a plan to interest galleries in selling original 16-mm prints to collectors, and he was one of the first avant-garde filmmakers to explore video sales. After selling VHS tapes of Jordan’s films for many years, Facets Multimedia has recently released a four-disc Lawrence Jordan Album. Its twenty-five films represent little more than half the titles in the filmmaker’s oeuvre. If Belson and Anger had established their reputations with startling rapidity by the time Jordan even began making films in 1952, Jordan has since become by far the most prolific of the three. By contrast, Belson has made some thirty short films since 1947 and Anger sixteen.” (from Sitney, P. Adams. “Moments of Illumination” Art Forum. https://www.artforum.com/print/200904/moments-of-illumination-the-films-of-lawrence-jordan-22308 April 2009. Retrieved July 2021)

Stan Brakhage (1933-2003) was an American filmmaker who is considered one of the most significant figures in experimental film.

“Over the course of five decades, Brakhage created a large and diverse body of work, exploring a variety of formats, approaches and techniques that included handheld camerawork, painting directly onto celluloid, fast cutting, in-camera editing, scratching on film, collage film and the use of multiple exposures. Interested in mythology and inspired by music, poetry, and visual phenomena, Brakhage sought to reveal the universal, in particular exploring themes of birth, mortality, sexuality, and innocence. His films are for the most part silent.

Brakhage’s films are often noted for their expressiveness and lyricism.” (from “Stan Brakhage” Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stan_Brakhage Retrieved June 2021)

Click here to view “Brakhage” a documentary by Jim Shedden on Kanopy

Robert Breer (1926-2011) was an American visual artist and filmmaker. His film work often combined abstract imagery with bits of rotoscoping..

“Robert Breer was most well known for his films, which combine abstract and representational painting, hand-drawn rotoscoping, original 16mm and 8mm film footage, photographs, and other materials His aesthetic philosophy and technique were influenced by an earlier generation of abstract filmmakers that included Hans Richter, Viking Eggeling, Walter Ruttmann, and Fernand Léger, whose work he discovered while living in Europe. Breer was also influenced by the concept of Neo-plasticism as described by Piet Mondrian and Vasarely.

After experimenting with cartoon animation as a child, he started making his first abstract experimental films while living in Paris from 1949 to 1959, a period during which he also showed paintings and kinetic sculptures at galleries such as the renowned Galerie Denise René.”(from “Robert Breer” UbuWeb https://www.ubu.com/film/breer.html Retrieved June 2021)

Click here to see “Screening Room with Robert Breer”, interview and short films on Kanopy.

Below is a clip from Breer’s animation Form Phases IV (1954).

Early Experiments in Computer Animation

“John Whitney, Sr (1917-1995) was an American animator, composer and inventor, widely considered to be one of the fathers of computer animation. In the 1940s and 1950s, he and his brother James created a series of experimental films made with a custom-built device based on old anti-aircraft analog computers (Kerrison Predictors) connected by servos to control the motion of lights and lit objects — the first example of motion control photography. One of Whitney’s best known works from this early period was the animated title sequence from Alfred Hitchcock’s 1958 film Vertigo, which he collaborated on with graphic designer Saul Bass. In 1960, Whitney established his company Motion Graphics Inc, which largely focused on producing titles for film and television, while continuing further experimental works. In 1968, his pioneering motion control model photography was used on Stanley Kubrick’s movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, and also for the slit-scan photography technique used in the film’s “Star Gate” finale.” (from “History of Computer Animation” Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_computer_animation Retrieved June 2021)

“Peter Foldes (1924-1977) was a pioneer in computer animation, which he introduced in Metadata, using the National Research Council of Canada’s computer. The film was made in collaboration with NRCC scientists Nestor Burtnyk and Marceli Wein, regarded in Canada as the fathers of computer animation technology. To tackle the themes of poverty and world hunger, Foldes again used computer animation in his Oscar-nominated Hunger (1974), doing line drawings of key frames and letting the computer create the transformations from one scene to another. Note similarity of man morphing into auto in Hunger with the Tron riders merging into their light cycles. Made for the National Film Board of Canada, Hunger won the Jury Prize at the 1974 Cannes Film Festival.

Born in Budapest, Foldes moved to England in 1946 and studied at the Slade School of Art. Later, he lived and worked in Paris. His other films include Animated Genesis (1952), A Short Vision (1956), Plus Vite (1965), Visages des femmes (1968), Je. Tu. Elles./I. You. They. (1972), Réve (1977) and Envisage (1977). He also worked on the computer graphics for the 1973 BBC-TV mini-series The Ascent of Man (1973). A Short Vision, his collaboration with Joan Foldes about a nuclear holocaust, was shown on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1956.” (from “Peter Foldes” Monoskop.org https://monoskop.org/Peter_Foldes Retrieved June 2021)

Hunger was produced by the Film Board of Canada in 1973. It was the first film that used computers to replicate the animation model of keyframes and in-betweens. In Hunger, a computer created the in-betweens.

Overview of 1960s and 70s youth movement

“The counterculture of the 1960s was an anti-establishment cultural phenomenon that developed throughout much of the Western world between the mid-1960s and the mid-1970s. The aggregate movement gained momentum as the U.S. Civil Rights Movement continued to grow, and, with the expansion of the American Government’s extensive military intervention in Vietnam, would later become revolutionary to some.As the 1960s progressed, widespread social tensions also developed concerning other issues, and tended to flow along generational lines regarding human sexuality, women’s rights, traditional modes of authority, experimentation with psychoactive drugs, and differing interpretations of the American Dream. Many key movements related to these issues were born or advanced within the counterculture of the 1960s.

As the era unfolded, what emerged were new cultural forms and a dynamic subculture that celebrated experimentation, modern incarnations of Bohemianism, and the rise of the hippie and other alternative lifestyles. This embrace of creativity is particularly notable in the works of musical acts such as the Beatles and Bob Dylan, as well as of New Hollywood filmmakers, whose works became far less restricted by censorship. Within and across many disciplines, many other creative artists, authors, and thinkers helped define the counterculture movement. Everyday fashion experienced a decline of the suit and especially of the wearing of hats; styles based around jeans, for both men and women, became an important fashion movement that has continued up to the present day.” (from ‘Counterculture of the 1960s” Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Counterculture_of_the_1960s Retrieved July 2021)

“At its height in the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement drew children, teenagers, and young adults into a maelstrom of meetings, marches, violence, and in some cases, imprisonment. Why did so many young people decide to become activists for social justice? Joyce Ladner answers this question in her interview with the Civil Rights History Project, pointing to the strong support of her elders in shaping her future path: “The Movement was the most exciting thing that one could engage in. I often say that, in fact, I coined the term, the ‘Emmett Till generation.’ I said that there was no more exciting time to have been born at the time and the place and to the parents that movement, young movement, people were born to… I remember so clearly Uncle Archie who was in World War I, went to France, and he always told us, ‘Your generation is going to change things.’” (from “Youth in the Civil Rights Movement” Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/collections/civil-rights-history-project/articles-and-essays/youth-in-the-civil-rights-movement/ Retrieved July 2021)

Animated films for the youth audience

Since a distinct youth market had developed, characterized by a questioning of authority and irreverence for traditions of the past, there were feature films as well as other media created to appeal to this audience. Yellow Submarine (1968), directed by George Dunning, uses the music of the Beatles to tell a fantasy adventure story. It is characterized by brilliant color and a surreal visual style.

“So Brodax began gathering together a team of creative collaborators, including Canadian animator George Dunning, visual effects director Charles Jenkins, The Beatles cartoon vets Jack Stokes and Mike Stuart and several screenwriters, including Latin professor and future Love Story novelist Erich Segal. (Liverpudlian poet Roger McGough would be brought on later to scouse things up; his lack of proper credit for giving the film a regional sense of cheekiness is still a point of contention.) It was Jenkins who suggested adding Heinz Edelmann, a Czech-German graphic artist best known for his work on the magazine Twen and who’d be the person most associated with the movie’s fluid, lysergic look. (He was also the one who suggested that they construct the narrative as a series of shorts, “so the style should vary every five minutes or so, to keep the interest going.”) The story goes that the group was having trouble deciding on a direction when Sir George Martin gathered them together in 1967 and played them the Beatles’ unreleased new album: Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Suddenly, there was a focal point to rally around. Those Summer of Love dandies in their marching band regalia? That everything-including-the-kitschin’-sink methodology? The pomo boho references piled upon references? They could start to set sail now.” (from Fear, David. “‘Yellow Submarine’ at 50: Why the Psychedelic Animated Beatles Movie Is Timeless”. Rolling Stone https://www.rollingstone.com/movies/movie-features/yellow-submarine-at-50-why-the-psychedelic-animated-beatles-movie-is-timeless-696384/ Retrieved July 2021)

Fantastic Planet (La Planète sauvage) (1973) is an animated science fiction film. An international production, directed by French filmmaker René Laloux (1929-2004), who co-wrote the script with French illustrator Roland Topor and animated at the Czech Jiří Trnka Studio.

“Born in 1929, Laloux wanted to become a painter. Biographers note that in the mid-50s he took on several different jobs to get by; he was subsequently employed by the Cour-Cheverny psychiatric clinic, run by the doctor Jean Oury, where he put on puppet shows with his patients. In 1960, his first short film, Les dents du singe, written and drawn by the clinics patients, drew attention to this thirty-something with progressive ideas and unusual therapeutic methods. This rather striking piece of work immediately made a mark, winning the Prix Emile Cohl.

In 1964, he started directing professionally, making another short with Roland Topor, Les temps morts, followed in 1965 by his most well known short film, Les escargots. It was quite natural for Laloux the puppeteer to turn to paper cutouts for these three films; a choice dictated as much by taste as by necessity (puppets and cutouts being directly animated under the camera). Les temps morts is an anti-militarist film, shot through with Topors black humor. Its crosshatched graphic style, which looks rather like etching, became Laloux trademark signature up until La planète sauvage.

Les escargots presents us with an everyday fantasy world: a gardener, growing lettuces, unwittingly sets off a series of catastrophes. The film won numerous international prizes, including the Grand Prix at the Mamaïa Festival (Romania) and the Special Jury Prize at the Cracow Festival. Whereas Laloux was still an unkown, Topor had already made something of a name for himself: an engraver, illustrator, screenwriter, he also wrote novels and short stories. By the late 60s his artistic work had achieved an international reputation, and his work was exhibited in London, New York and Chicago. Laloux himself continued to paint, but without ever really making his name in this field.

His collaboration with Topor led to the making of the animated feature, La planète sauvage. Laloux, a science fiction fan, persuaded Topor to work on an adaptation of the work of Stefan Wul, one of the best French writers in the genre. A dental surgeon, Wul had written a dozen sci-fi novels in his spare time, published in the highly popular Anticipation series in the mid 50s by Fleuve Noir, which also specialized in detective and espionage thrillers. The covers, designed by the illustrator Brantonne, were not dissimilar to American publications such as Amazing Stories and Astounding Stories of the preceding generation. But content-wise, they could not have been more different.” (from Moins, Phillipe. “René Laloux, The Man Who Made ‘La Planète Sauvage’ (‘The Fantastic Planet’)”. Animation World Network https://www.awn.com/animationworld/ren-laloux-man-who-made-la-plan-te-sauvage-fantastic-planet May 10, 2004. Retrieved July 2021)

Ralph Bakshi

Ralph Bakshi (born 1938) is an American director and animator. He began his career working in television at Terrytoons. He started his own studio, Bakshi Productions in 1968. Fritz the Cat (1972), his first feature, was based on cartoonist Robert Crumb’s comic strip. He went on to direct a number of other features, including Wizards (1977), The Lord of the Rings (1978),

“It will come as a surprise to many that Mr. Bakshi, the brash, street-smart Bad Boy of Animation, needs more confidence, courage or heart. The 41-year-old animator-turned-director began his feature career in 1972 with the first X-rated animated cartoon, ”Fritz the Cat,” which cost only $750,000 at a time when the Disney studio was spending $6 million remaking ”Robin Hood” with talking animals, but made about the same amount of money (between $25 million and $30 million worldwide).

After his third feature, ”Coonskin,” which he says he intended as ”an attack on hypocrisy in all races,” was itself attacked by the Congress On Racial Equality (C.O.R.E.) as racist and was hastily withdrawn from distribution by Paramount Pictures, Mr. Bakshi made a strategic retreat to Disney territory – and won a stunning victory. His version of J.R.R. Tolkein’s sword-and-sorcery classic, ”Lord of the Rings,” cost $8 million and has earned worldwide rentals to date of between $45 million and $50 million, while satisfying most film critics and Tolkein cultists. But Mr. Bakshi’s unrepentant response to the success of ”Rings” was to return to his one-man Ashcan School of Animation.” (from Culhane, John. “Ralph Bakshi – Iconoclast of Animation” New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/1981/03/22/arts/ralph-bakshi-iconoclast-of-animation.html Retrieved July 2021)

Terry Gilliam (born 1940) is an American born British animator and filmmaker who was part of the Monty Python comedy troupe. He made animated segments for their film and television productions. His surrealistic clips tied together the live action sketches of the group. Their series Monty Python’s Flying Circus, ran on the BBC from 1069-1974 and they made several feature films as well.

“Before he directed such mind-bending masterpieces as Time Bandits, Brazil and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, before he became short-hand for a filmmaker cursed with cosmically bad luck, before he became the sole American member of seminal British comedy group Monty Python, Terry Gilliam made a name for himself creating odd animated bits for the UK series Do Not Adjust Your Set. Gilliam preferred cut-out animation, which involved pushing bits of paper in front of a camera instead of photographing pre-drawn cels. The process allows for more spontaneity than traditional animation along with being comparatively cheaper and easier to do.

Gilliam also preferred to use old photographs and illustrations to create sketches that were surreal and hilarious. Think Max Ernst meets Mad Magazine. For Monty Python’s Flying Circus, he created some of the most memorable moments of a show chock full of memorable moments: A pram that devours old ladies, a massive cat that menaces London, and a mustached police officer who pulls open his shirt to reveal the chest of a shapely woman. He also created the show’s most iconic image, that giant foot during the title sequence.” (from “Terry Gilliam Reveals the Secrets of Monty Python Animations: A 1974 How-To Guide” Open Culture. https://www.openculture.com/2020/11/terry-gilliam-reveals-the-secrets-of-monty-python-animations-a-1974-how-to-guide.html November 6, 2020 Retrieved July 2021)

Below is a clip from And Now for Something Completely Different (1971) animated by Gilliam.

From arcade games to personal consoles

“The roots of the American arcade can be traced back to the dime museums, exposition midways, and amusements parlors of the 19th century. At the end of that century, parlor owners filled their establishments with such new novelties of the Industrial age as phonographs, kinetoscopes, and mutoscopes. These inventions provided parlor goers with the magical experiences of listening to recorded sounds and watching moving images. However, by the turn of the century, as the novelty of those inventions wore off, many amusement parlors transformed into penny arcades. When arcade owners repurposed these spaces, the character of their establishments also began to change as the crowds of refined men and women willing to pay as much as 25 or 50 cents to view kinetoscope films were replaced by throngs of nearby office workers, tourists, vacationers, shoppers, and young, working-class men. Arcade patrons flocked to coin-operated peep show machines, shooting galleries, grip and strength testers, stationary bicycles, slot machines (in some areas), machines that dispensed fortunes or candy, and other mechanical amusements they could play for as little as a penny. (from Saucier, Jeremy. “Coin-Op Century: A Brief History of the American Arcade” Museum of Play https://www.museumofplay.org/blog/chegheads/2013/05/coin-op-century-a-brief-history-of-the-american-arcade Retrieved July 2021)

“The introduction of arcade video games during the early to middle 1970s pushed pinball and electromechanical games out of many arcades. Pinball, it seemed, couldn’t compete with the blips and bloops of Pong (1972) while Speedway couldn’t match the excitement of navigating a glowing race car in Gran Trak 10 (1974). By the early 1980s, video games were a cultural phenomenon and arcades had transformed again, becoming “video arcades.” Indeed, according to Play Meter magazine, by 1981 there were approximately 24,000 full arcades with thousands more non-arcade locations including restaurants, gas stations, and dentist offices all over the United States. An oversaturated market for arcade games, improved home video game consoles, and rekindled anxieties about the relationship between arcades and juvenile delinquency (among other things) all contributed to the decline of video arcades by the end of the 20th century.” (from Saucier Coin-Op Century: A Brief History of the American Arcade”)

“In 1967, developers at Sanders Associates, Inc., led by Ralph Baer, invented a prototype multiplayer, multi-program video game system that could be played on a television. It was known as “The Brown Box.”

“Baer, who’s sometimes referred to as Father of Video Games, licensed his device to Magnavox, which sold the system to consumers as the Odyssey, the first video game home console, in 1972. Over the next few years, the primitive Odyssey console would commercially fizzle and die out.

Yet, one of the Odyssey’s 28 games was the inspiration for Atari’s Pong, the first arcade video game, which the company released in 1972. In 1975, Atari released a home version of Pong, which was as successful as its arcade counterpart.

Magnavox, along with Sanders Associates, would eventually sue Atari for copyright infringement. Atari settled and became an Odyssey licensee; over the next 20 years, Magnavox went on to win more than $100 million in copyright lawsuits related to the Odyssey and its video game patents.

In 1977, Atari released the Atari 2600 (also known as the Video Computer System), a home console that featured joysticks and interchangeable game cartridges that played multi-colored games, effectively kicking off the second generation of the video game consoles.

The video game industry had a few notable milestones in the late 1970s and early 1980s, including:

- The release of the Space Invaders arcade game in 1978

- The launch of Activision, the first third-party game developer (which develops software without making consoles or arcade cabinets), in 1979

- The introduction to the United States of Japan’s hugely popular Pac-Man

- Nintendo’s creation of Donkey Kong, which introduced the world to the character Mario

- Microsoft’s release of its first Flight Simulator game”

(from “Video Game History” History.com https://www.history.com/topics/inventions/history-of-video-games Retrieved July 2021)

Types of games

Early on in the development of games, a variety of genres appeared, including puzzle games, platform games, role playing games, simulations and educational games.

Puzzle Games

“Puzzle games focus on logical and conceptual challenges. While many action games and adventure games include puzzle elements in level design, a true puzzle game focuses on puzzle solving as its primary gameplay activity.[1]

Rather than presenting a random collection of puzzles to solve, puzzle games typically offer a series of related puzzles that are a variation on a single theme. This theme could involve pattern recognition, logic, or understanding a process. These games usually have a set of rules, where players manipulate game pieces on a grid, network or other interaction space. Players must unravel clues in order to achieve some victory condition, which will then allow them to advance to the next level. Completing each puzzle will usually lead to a more difficult challenge.

Puzzle games can include:

- Matching objects based on categories (e.g. patterns, colors, shapes, symbols, etc.)

- Visualizing and manipulating objects in space and time

- Memorizing complex patterns

- Tackling increasing complexities of puzzles that build upon previous puzzles

- Solving puzzles under a time constraint or limited-life constraint.

- Applying previous-known knowledge about the world

- Thinking outside of the box”

(from “Puzzle Video Game”. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Puzzle_video_game Retrieved July 2021)

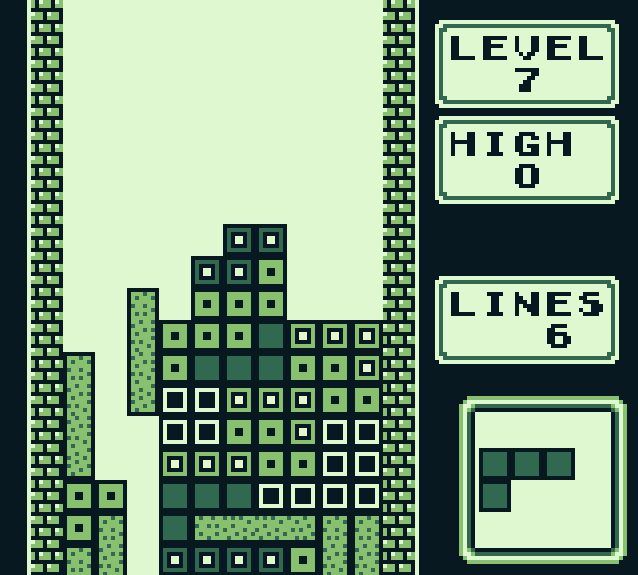

Tetris is perhaps one of the best known puzzle games. It was developed by Soviet game designer Alexey Pajitnov in 1984 and remains extremely popular,

Platform games

“A platform game requires the player to manoeuvre their character across platforms to reach a goal, while confronting enemies and avoiding obstacles along the way. These games are either presented from the side view, using two-dimensional movement, or in 3D with the camera placed either behind the main character or in isometric perspective. The typical platforming gameplay tends to be very dynamic, and challenges a player’s reflexes, timing, and dexterity with controls.

The most common movement options in the genre are walking, running, jumping, attacking, and climbing. Jumping is the key element of the gameplay in all platform games, and can be categorized as either “committed” or “variable”; wherein the trajectory of a committed jump cannot be changed mid-air, that of a variable jump can. In some platform games, falling from considerable heights may cause damage, possibly even leading to death. Many platform games feature zones within the game world that would kill the player character instantly upon contact, such as lava pits or bottomless chasms. Through the various areas of the game world, player may be able to collect items and powerups that can come in handy for different situations, and give the main character new abilities that can make it easier for him to face adversities.” (“Platform game”. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Platform_game Retrieved July 2021)

Donkey Kong was developed by Nintendo as an arcade game in 1981. Mario Bros, another platform game, was designed by Shigeru Miyamoto for Nintendo in 1983.

Role Playing Games

“Role-playing video game, electronic game genre in which players advance through a story quest, and often many side quests, for which their character or party of characters gain experience that improves various attributes and abilities. The genre is almost entirely rooted in TSR, Inc.’s Dungeons & Dragons (D&D; 1974), a role-playing game (RPG) for small groups in which each player takes some role, such as a healer, warrior, or wizard, to help the player’s party battle evil as directed by the group’s Dungeon Master, or assigned storyteller. While fantasy settings remain popular, video RPGs have also explored the realms of science fiction and the cloak-and-dagger world of espionage.” (from “Role-playing video game” Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/role-playing-video-game Retrieved July 2021)

Simulations

“A simulation video game describes a diverse super-category of video games, generally designed to closely simulate real world activities.

A simulation game attempts to copy various activities from real life in the form of a game for various purposes such as training, analysis, prediction, or simply entertainment. Usually there are no strictly defined goals in the game, with the player instead allowed to control a character or environment freely.[2] Well-known examples are war games, business games, and role play simulation.” (from “Simulation video game” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Role-playing_video_game Retrieved July 2021)

“The desire to simulate reality—to establish a set of rules and systems that represent some aspect of life—seems inherent in all of us. Children play house, have tea parties with invisible tea, and pretend to be cops, robbers, astronauts, explorers, or doctors. Eventually, those children grow up to be game developers, and they start cranking out digital sims of nearly every imaginable activity.” (from Moss, Richard. “From SimCity to Real Girlfriend: 20 years of sim games” Ars Technica. https://arstechnica.com/gaming/2011/06/history-of-sim-games-part-1/ June 20, 2011 Retrieved July 2021)

Educational games

“As early as the first microcomputers in the late 1970s, gaming and education have gone hand-in-hand. Early educational gaming pioneers like MECC, Davidson, and the Learning Company created innovative titles that inspired the Atari generation and beyond. Computer labs began to spring up in school across North America and the world. Students gleefully munched numbers, typed with Mavis, and guided wagons across the American frontier. Soon, the floppy disk gave way to CD-ROM, as technology continued to advance. The 1990s became the age of the PC, as families around the world invited in a new member of the family into their homes. By the 2000s we were wired and well connected, as people all over the world interacted over the world wide web. A new era of gaming would be ushered in with the proliferation of the internet, where people could play, share, and learn together from thousands of miles away. Touch screens, apps and other modern innovations have propelled the gaming industry forward even further, leaving educators and game developers positively giddy over the possibilities.” (from “history” Game Based Learning https://blogs.ubc.ca/gamebasedlearning/history/ Retrieved July 2021)

Online gaming

“Long before gaming giants Sega and Nintendo moved into the sphere of online gaming, many engineers attempted to utilize the power of telephone lines to transfer information between consoles.

William von Meister unveiled groundbreaking modem-transfer technology for the Atari 2600 at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas in 1982. The new device, the CVC GameLine, enabled users to download software and games using their fixed telephone connection and a cartridge that could be plugged in to their Atari console.

The device allowed users to “download” multiple games from programmers around the world, which could be played for free up to eight times; it also allowed users to download free games on their birthdays. Unfortunately, the device failed to gain support from the leading games manufacturers of the time, and was dealt a death-blow by the crash of 1983.

Real advances in “online” gaming wouldn’t take place until the release of 4th generation 16-bit-era consoles in the early 1990s, after the Internet as we know it became part of the public domain in 1993. In 1995 Nintendo released Satellaview, a satellite modem peripheral for Nintendo’s Super Famicom console. The technology allowed users to download games, news and cheats hints directly to their console using satellites. Broadcasts continued until 2000, but the technology never made it out of Japan to the global market.” (from Chikhani, Riad. “The History Of Gaming: An Evolving Community” https://techcrunch.com/2015/10/31/the-history-of-gaming-an-evolving-community/ October 31, 2015. Retrieved July 2021)

“The history of online games dates back to the early days of packet-based computer networking in the 1970s, An early example of online games are MUDs, including the first, MUD1, which was created in 1978 and originally confined to an internal network before becoming connected to ARPANet in 1980. Commercial games followed in the next decade, with Islands of Kesmai, the first commercial online role-playing game, debuting in 1984, as well as more graphical games, such as the MSX LINKS action games in 1986, the flight simulator Air Warrior in 1987, and the Famicom Modem’s online Go game in 1987.

The rapid availability of the Internet in the 1990s led to an expansion of online games, with notable titles including Nexus: The Kingdom of the Winds (1996), Quakeworld (1996), Ultima Online (1997), Lineage (1998), Starcraft (1998), Counter-Strike (1999) and EverQuest (1999). Video game consoles also began to receive online networking features, such as the Famicom Modem (1987), Sega Meganet (1990), Satellaview (1995), SegaNet (2000), PlayStation 2 (2000) and Xbox (2001). ” (from “Online games” Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Online_game Retrieved July 2021)

Indie games

While much of the production of video games is controlled by a few companies, games are also produced by individuals and independent companies. Distribution can be an issue however. Sometimes indie games have been distributed as shareware, or with a free trial version. Currently, Kickstarter has become a platform for funding and for distributing indie games.

“Indie game development bore out from the same concepts of amateur and hobbyist programming that grew with the introduction of the personal computer and the simple BASIC computer language in the 1970s and 1980s.” (from “Indie game”. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indie_game Retrieved July 2021)

“Indie games generally share certain common characteristics. One method to define an indie game is the nature of independence, which can either be:

- Financial independence: In such situations, the developers have paid for the development and/or publication of the game themselves or from other funding sources such as crowd funding, and specifically without financial support of a large publisher.

- Independence of thought: In this case, the developers crafted their game without any oversight or directional influence by a third party such as a publisher.

Another means to evaluate a game as indie is to examine its development team, with indie games being developed by individuals, small teams, or small independent companies that are often specifically formed for the development of one specific game. Typically, indie games are smaller than mainstream titles. Indie game developers are generally not financially backed by video game publishers, who are risk-averse and prefer “big-budget games”. Instead, indie game developers usually have smaller budgets, usually sourcing from personal funds or via crowdfunding. Being independent, developers do not have controlling interests[4] or creative limitations, and do not require the approval of a publisher, as mainstream game developers usually do. Design decisions are thus also not limited by an allocated budget. Furthermore, smaller team sizes increase individual involvement.” (from “Indie game”. Wikipedia)

Issues in the gaming community

Gamergate

“Like all hashtags, #Gamergate has come to mean about 500 different things to thousands of different people. But at its heart, it’s about two topics:

1) The treatment of women in gaming: The start of the story (which is actually the latest permutation of a long-evolving firestorm) came in late August after indie game developer Zoe Quinn and gaming critic Anita Sarkeesian were both horribly harassed online. The same harassment was later lobbed at award-winning games journalist Jenn Frank and fellow writer Mattie Brice. Both Frank and Brice say they will no longer write about games. The FBI is looking into harassment of game developers.

2) Ethics in games journalism: The Gamergaters argue that the focus on harassment distracts from the real issue, which is that indie game developers and the online gaming press have gotten too cozy. There’s also a substantial, vocal movement that believes the generally left-leaning online gaming press focuses too much on feminism and the role of women in the industry, to the detriment of coverage of games. (One of the sites mentioned in this debate is Vox’s sister site Polygon.) These concerns exploded after programmer Eron Gjoni, who had dated Quinn, posted a revenge blog accusing her of cheating on him with Nathan Grayson, a writer for the influential games website Kotaku.” (from VanDerWerff, Emily. “#Gamergate: Here’s why everybody in the video game world is fighting” https://www.vox.com/2014/9/6/6111065/gamergate-explained-everybody-fighting Oct 13, 2014. Retrieved July 2021)

Lack of diversity in game developer community

“Three out of four people working in the gaming industry are men. Almost the same proportion identifies as white. And those numbers have hardly budged since 2015, according to surveys conducted by the nonprofit International Game Developers Association.

“If you’re a young person of color playing games, you don’t really see yourself represented,” said Mitu Khandaker, a professor at New York University’s game center. “That kind of instills in you this sense that maybe I don’t really belong.”

That lack of diversity in mainstream gaming — games made by the handful of large development companies — can be cyclical, turning people away from the industry, said Dr. Khandaker, who is also the chief executive of Glow Up Games, a research and development studio focused on diversity.

Women, for example, are rarely promoted to senior positions or made the heads of studios. Many gamers say toxic harassment online is still an everyday fear.

Some like Mr. Gooden, 21, see signs of hope. He started making games shortly after he got his first laptop in the fifth grade and discovered a game-developing program online. He never stopped. In Mr. Gooden’s role-playing game, She Dreams Elsewhere, the main character, Thalia Sullivan, navigates her own mind, battling nightmares as she tries to eventually figure out how she fell into a coma.

The most recent I.G.D.A. survey found that 81 percent of those in the industry feel that diversity in the workplace is either very important or somewhat important, up from 63 percent in 2015.

And developers have more outlets to get their games in the hands of players, including online platforms like Steam and crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter, as well as gaming conferences and festivals.

“I’m an optimist,” Mr. Gooden said. “I hope that things will eventually be better as a whole.”” (from Zaveri, Mihir et al “Fear, Anxiety and Hope: What It Means to Be a Minority in Gaming” https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/10/16/technology/game-developers.html Oct. 16, 2019 Retrieved July 2021)

ASSIGNMENT: Long paper thesis or outline

Review the long paper guideline and grading rubric and submit a thesis or outline as a journal entry by next week. Visit this page for more information.