The Rise of Television

We will look at how Television changed the animation industry, and launched new animation studios, techniques, genres, and audiences.

Jump to the different sections with the links below:

Overview of Television’s Rise | Puppets in Early Children Programming | New Studios Dedicated to TV Animation |Hanna-Barbera Productions, Inc. | Educational Programming | Product-driven Shows | Disney and TV | TV Animation for Adults | Music-videos | Japanese TV Animation |Introduction to Long Paper Guidelines and Grading Rubric | Assignment

Overview of Television’s Rise

“Electronic television was first successfully demonstrated in San Francisco on Sept. 7, 1927. The system was designed by Philo Taylor Farnsworth, a 21-year-old inventor who had lived in a house without electricity until he was 14. While still in high school, Farnsworth had begun to conceive of a system that could capture moving images in a form that could be coded onto radio waves and then transformed back into a picture on a screen. Boris Rosing in Russia had conducted some crude experiments in transmitting images 16 years before Farnsworth’s first success. (…) RCA, the company that dominated the radio business in the United States with its two NBC networks, invested $50 million in the development of electronic television.(…) In 1939, RCA televised the opening of the New York World’s Fair, including a speech by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was the first president to appear on television. (…) RCA began selling television sets with 5 by 12 in (12.7 by 25.4 cm) picture tubes. The company also began broadcasting regular programs, including scenes captured by a mobile unit and, on May 17, 1939, the first televised baseball game between Princeton and Columbia universities.(…) World War II slowed the development of television, as companies like RCA turned their attention to military production. (…) Six experimental television stations remained on the air during the war – one each in Chicago, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Schenectady, N.Y., and two in New York City. But full-scale commercial television broadcasting did not begin in the United States until 1947.(…) The number of television sets in use rose from 6,000 in 1946 to some 12 million by 1951. No new invention entered American homes faster than black and white television sets; by 1955 half of all U.S. homes had one.” (from Grolier Encyclopedia and Mitchell Stephens)

Television was one of the most important appliances in shaping the post-war American lifestyle: it provided “at home” entertainment for newly built suburban communities, and encouraged the purchase of products through advertising (most TV shows were sponsored directly by manufacturers of consumer goods).

Most TV shows were broadcasted live until the advent of videotaping in 1956 (except for a few instances of 16mm or 35mm recordings). The image quality on early TV sets was were very low given the screen’s small size and the unpredictable signal reception. The use of antennas and cable in the late 1940s improved the broadcast delivery. While the technology for broadcasting and receiving color images existed early on, it wasn’t widely adopted until 1965 due to the high cost of color TV sets.

Animation was at the forefront of the development of the TV industry: In 1929, an image of Felix the Cat (see week 3) was selected for the first experimental broadcast in the US. When NBC, the first network, launched its first night of broadcasting in NYC in 1939, it premiered a Disney short (“Donald’s Cousin Gus” by Jack King).

Puppets in Early Children Programming

Early TV children programming often featured puppets, as the format was relatively inexpensive to produce. One of the earliest and most popular of these puppet-centric productions was “Kukla, Fran, and Ollie” (1947 to 1957) (see episode from 1949 below (30 min) ) which was created and puppeteered by Burr Tillstrom. The show (which ran on NBC and later ABC), was mostly unscripted and consisted of “host Fran Allison standing in front of a puppet stage and interacting with Kukla and Ollie, the two puppet stars of the show, along with a host of other puppet characters. The secret to the show’s success was that it combined a simple format and seemingly gentle, sweet atmosphere with adult-level wit and sly satire. (…) When you watch old videos of the show today, you can hear the crew laughing off-screen during some of the funnier moments. They were apparently as surprised and entertained by the unscripted comedy as the viewers at home were.” (from Classic Kids TV)

An early TV recording, with the Kinescope technology (16mm film): “Kukla, Fran and Ollie – Babysitter Show” (February 24, 1949) (30min)

“Howdy Doody” (1947-1960) (see episode from March 1949 below (29 min)), also on NBC, was another popular puppet TV show. The character of Howdy Doody, a freckle-faced boy marionette with 48 freckles, one for each state of the union at the time, was created by radio personality Buffalo Bob Smith during his days as a radio announcer on WNBC. Smith would continue to voice the character on TV. “The name of the puppet “star” was derived from the American expression “howdy doody”/”howdy do,” a commonplace corruption of the phrase “How do you do?” used in the western United States. (The straightforward use of that expression was also in the theme song’s lyrics.) Smith, who had gotten his start as a singing radio personality in Buffalo, frequently used music in the program. Cast members Lew Anderson and Robert “Nick” Nicholson both were experienced jazz musicians. (…) As both the character and television program grew in popularity, demand for Howdy Doody-related merchandise began to surface. By 1948, toymakers and department stores had been approached with requests for Howdy Doody dolls and similar items. It was one of the first television shows with audience participation as a major component. [The show] was also a pioneer in early color production: NBC used the show in part to sell color television sets in the 1950s.” (from Wikipedia)

Early experiments with interactive screens can also be traced to early children TV programs: “First aired in 1953, “Winky Dink and You” (1953-1957) (see 30 min episode below) was hosted by Jack Barry, a famous television personality since the beginning of television broadcasting. His animated sidekick, the titular Winky Dink, was voiced by Mae Questel, best known as the voice of Betty Boop and Olive Oyl. “Winky Dink said he wanted the children to mail away for a ‘Magic Window,’ which was actually a cheaply produced, thin sheet of plastic that adhered to the TV screen by static electricity,” writes Winky Dink-generation columnist Bob Greene. “Along with the plastic sheet that arrived in the mail were ‘magic crayons.’ Children were encouraged to place the sheet on their TV screen and watch the show each Saturday, so that Winky Dink could tell them what to do.” Winky Dink, and Barry, often told them to draw in the missing parts of a picture, or to connect dots that would reveal a coded message.” (from openculture.org)

New Studios Dedicated to TV Animation

The first “made-for-TV” animated series was “Crusader Rabbit” (1950 – 1952), which aired on NBC and was produced by Jay Ward Productions. The company was created by two friends: Alex Anderson (1920 – 2010), an animator at Terrytoons (a NY-based animation studio that produced animated cartoons for theatrical release from 1929 to 1972), and Jay Ward (1920 – 1989), an MBA Harvard grad. The animation was bare-bones: the vast majority of the sequences consisting of still drawings with voice-over narration.

The studio would develop several successful TV series, including “Rocky & His Friends” (1959 – 1964) (or “The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends”) (see episode 2: “Jet Fuel Formula” (1959) (23 min) below). Featuring a small and smart squirrel, and his friend, a large and somewhat naive moose. The show’s villains are Russian caricatures reflecting the Cold War era during which the show was broadcasted. The episodes’ main storylines are intercut with recurring vignettes such as “Fractured Fairytales” (see 5:38 min in episode below) and “Peabody’s Improbable History”. While the animation remained limited, the studio’s productions became popular for their witty-dialogue and subtextual humor.

Another successful character developed by the studio was “George of the Jungle” (1967). Jay Ward Productions also created memorable characters for advertising, such as General Mills Company’s Cap’ n Crunch (1962). They created long-format ads (see example from 1962 below) that were broadcasted between cartoons.

Several other animation studios dedicated solely to made-for-TV animation opened in the early 1960’s. While some of them were founded by filmmakers and animators that came from the world of theatrical animation, others were led by businessmen who were guided primarily by the financial potential they saw in children TV programming, and gave little attention to the quality of the stories and of the animation they produced.

One of the better known studios to emerge at this time was the DePatie-Freleng studio, founded in 1963. When Warner Bros Animation closed (see week 6) , many of its animators moved to DePatie-Freleng and the studio was contracted to create films for Warner Bros. The studio’s most famous original character is the Pink Panther. It first appeared in the animated credits of the live-action film of the same name (1963) (see credits sequence (4 min) below), and was then featured in its own TV series which aired on NBC in 1969.

While some of these new studios had an “in-house” animation team, many contracted animators abroad (mainly to cut cost). For example, Total TeleVision Productions which opened in 1959, and is responsible for the “Underdog” series and some well known General Mills ads and characters, used a Mexican studio Gamma Productions S.A. de C.V. for the realization of almost all its production (Jay Ward also used the studio in a few instances). The Czech studio Krátký Film Praha, and Halas & Batchelor (UK) (see week 8) were amongst the other international studios that were subcontracted to work on American TV cartoons.

Hanna-Barbera Productions, Inc.

William Hanna (1910 – 2001) and Joseph Barbera (1911 – 2006) were famous for directing “Tom & Jerry” shorts at MGM (see week 6). When the studio closed in 1957, they opened their own studio, Hanna-Barbera Productions, Inc., who would come to create some of the most memorable shows in television animation history, most of which were syndicated (leasing the rights to) and aired on many different TV channels throughout the years. Their first success was “The Huckleberry Hound Show” (1958-1992). It was critically-acclaimed, receiving an Emmy, and one of it’s side characters – Yogi Bear – got its own spinoff series a few years later.

But their next hit, would change the animation TV landscape forever: “The Flintstones” (1960 – 1966) was the first cartoon to air on primetime. Until then, animated series were relegated to Saturday mornings. “[Hanna and Barbera] agreed that, if [the show] was to survive in the primetime landscape, it had to incorporate the adult feel of other primetime series while being toned down enough that the whole family could enjoy it. At the time, with such shows as “Father Knows Best” and “Leave It to Beaver”, the most popular programs on primetime were sitcoms about suburban families, so they decided that would be the direction they’d go (including the laugh tracks). (…) A strong inspiration for [the show] was “The Honeymooners”, a popular 1950’s sitcom starring Jackie Gleason, which happened to be the only sitcom that Bill Hanna enjoyed at the time. He enjoyed how the laughs came from how the main characters were in a constant war of the sexes, while also presenting a much more realistic and relatable marriage rather than the perfect, seemingly flawless marriages that most other sitcoms tried to work with. (…) In early 1960, Joe Barbera took a 2 min test short of “The Flintstones”, as well as two storyboards which would later be made into the first and third episodes respectively, to New York City and pitched the show for eight straight weeks to as many sponsors and networks that would listen. On the very last day, exhausted and discouraged (and threatening to toss the concept into the archives never to be seen again), he pitched the show to executives at ABC. ABC, eager to take on risks and experimentation, signed on to the show only fifteen minutes into his 90 minute presentation. They picked the show up for a 28 episode first season, and The Flintstones began airing September 30th, 1960 at 8:30pm as part of ABC’s Friday night line-up (alongside long-running detective series “77 Sunset Strip” and a package show of Famous Studios cartoons entitled “Matty’s Funday Funnies”). (…) Barney Rubble’s [one of the main characters] finalized voice was provided by the famous “man of a thousand voices” himself, Mel Blanc (see week 6). With the theatrical animated short business drying up (though Warner Bros. held in longer than most animation studios), The Flintstones marked Mel Blanc’s transition to television. (…) The Flintstones was one of the first cartoons to create an emphasis on guest stars appearing voicing versions of themselves, all with rock-themed names. Such guest stars were Ed Sullivan (“Ed Sullystone”), Tony Curtis (“Stony Curtis”), Rock Hudson (“Rock Hudstone”), Cary Grant (“Cary Granite”), and most famously Ann-Margret (“Ann-Margrock”). For the time, being a guest star on the Flintstones was considered a mark of prestige. (…) During its first two and a half seasons, the Flintstones, while produced for all audiences, was targeted by ABC towards adult viewers. This is made most clear by the show’s original sponsor, Winston Cigarettes. During commercial breaks, the characters would be shown sitting around discussing Winston Cigarettes and lighting up a smoke, usually ending by reciting or singing the Winston jingle (“Winston tastes good like a cigarette should”). Once the story arc leading up to the birth of Pebbles began, and the show gradually aimed more towards younger viewers (an obviously inappropriate demographic to be pushing cigarettes towards), Winston pulled out of the show and the sponsorship spot was replaced by Welch’s. Welch’s went the extra mile and included the characters on their jelly jars, which were marketed as being reusable as drinking cups. (…) The Flintstones ran in prime-time on ABC for six seasons, occupying the 8:30pm Friday slot for half of its run. It concluded on April 1, 1966, with an impressive 166 episode run. Following the Flintstones success in primetime, many other series during the early 60’s attempted to capture that lightning in a bottle, creating a bit of an animation boom in primetime. ABC lead the helm, airing several other series by Hanna-Barbera (“The Jetsons”, “Top Cat”, and “Jonny Quest”). While some of these were successes in their own right, none of them held a candle to the fame that the Flintstones had gained.” (from reelrundown.com)

Wilma’s pregnancy in season 3 (1963) was pioneering in its realistic depiction of a pregnancy’s effect on a family’s financial and emotional situation – see excerpt below (2 min):

Educational Programming

“Sesame Street” started in 1969 and is still one of the most beloved and widely watched children’s television series in the world. The show achieves a great balance between humor, candor, and education rarely achieved in children programming. While Jim Hensons’ puppets are shot in live-action and are at the heart of the show, “Sesame Street” also includes animated sequences featuring a wide array of techniques and styles, including stop-motion sand animation for the “Sand Alphabet” series (1973 – 2001) (see letter “R” (0:15 min) (1977) below) , and very early, pre-Pixar CGI by John Lasseter and Andrew Stanton (using the characters of their Luxo Jr. short – see week 12) (see “Surprise” (1991) (o: 20 min) below).

“Schoolhouse Rock!” (1973 – 1984) was launched by ABC as a series of interstitial shorts aired between TV series and advertisements. The concept – to educate children through memorable songs and animation – was spearheaded by an advertising executive, David McCall, who hoped it would attract advertisers. Indeed, companies such as General Mills, Nabisco and Mattel were amongst the series many large sponsors over the years. Michael Eisner (head of children programming at ABC at the time, and later associated with Disney’s second “Golden Age” (see week 12) green-lit the project and brought in the legendary animator Chuck Jones (see week 6) to head the series’ animation. Much of “Schoolhouse Rock!”‘s success can also be attributed to Bob Dorough, a bebop and jazz composer who had worked with Miles Davis, and who composed and performed most of the original episodes. Another important figure associated with the series was Tom Yohe, an advertising agency veteran, who art directed some of the most memorable episodes. His children also provided the voices for some of the series’ characters. The show had a second run from 1993 – 1999 (combining old and new episodes) and the series’ rights was recently acquired by Disney+.

One one the most well-known episode (alongside’s “I’m Just a Bill” (1976)) is “Conjunction Junction” (1973) (3 min) (see below) which features Bob Dorough’s Music and Lyrics.

Product-driven Shows

The 1980s was the era of deregulations brought about by Ronald Reagan’s presidency. A lot of the rules around the production of TV children programming were loosened, leading to a new crop of animated shows built around the goal of selling toys. The term “toyetic” was used in the industry to describe series that would be conducive to the production and sale of merchandize. Most of these shows were outsources and cheaply produced.

“G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero” (1983-1986) and “Transformers” (1984 – 1987) (see “Cosmic Rust” (1985) Paul Davids (22 min) below) are the most well known examples of “toyetic” shows from that era. Both were syndicated, 30 min series, centered around toys by the Hasbro company. In the case of “G.I. Joe” the products predated the animated series by several decades. “Transformers” was inspired by the success of the Japanese “Gundam” series/action figures (see section below). In both cases, the animated series also led to an expansion of the product line, films, live-action series, comics, and even breakfast cereal. Both franchises are still owned by Hasbro which continues to manufacture the toys, and new series and films are still being developed (see the Hasbro website for both lines – Transformers; G.I. Joe)

Disney and TV

Disney saw the power of TV early on and created pioneering, beloved shows for children. “In 1948 [Walt Disney] spent a week in New York with the specific purpose of watching and learning more about television. By the time he returned to the Studio, he was convinced it was just the forum to help promote his work (including Disneyland which was being built and would open in 1955). While other movie studios were trying to think of ways to thwart the coming of television, Walt was gearing up to embrace it.(…) On Christmas Day, 1950, Walt Disney Productions aired its first ever television special. “One Hour in Wonderland” (see except – 18 min – below) was a charming concoction of cartoon clips (including previews of the yet-to-be-released “Alice in Wonderland”), appearances from stars of the day, and Walt Disney himself.(…) “One Hour in Wonderland” was a huge success, and Walt followed it with another special the following Christmas, “The Walt Disney Christmas Show”. (…) With the estimated cost of Disneyland exceeding what Walt was able to raise on his own, he realized that a weekly television series would bring in much-needed revenue. He also remembered its potential for promotion. “Every time I’d get to thinking of television I would think of this Park. And I knew that if I did anything like the Park that I would have some kind of medium like television to let people know about it,” Walt said. In September of 1953, the Studio created outlines for four different shows: “The Walt Disney Show”, “Mickey Mouse Club TV Show”, “The True Life TV Show”, and “The World of Tomorrow”. After several months of negotiations with all three major networks (ABC, CBS, NBC), Disney struck a deal with ABC to bring the simply titled “Disneyland” series to television sets across America. The first episode, “The Disneyland Story”, premiered on October 27, 1954. Over the years, the show has undergone several title changes (“Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color”, “Disney’s Wonderful World”, “The Disney Sunday Movie”, “The Magical World of Disney”—just to name a few), and has aired on all three major networks. The anthology series—known for bringing beloved characters like Zorro and Davy Crockett to the screen, as well as the groundbreaking “Man in Space”—is the second longest running prime-time program in the history of American television.

“One Hour In Wonderland”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8WmD1Xt-MaY

Despite these early TV shows centered around live-action series, short documentaries, and repurposed theatrical shorts, the studio was relatively late in developing series specifically for TV. It wasn’t until 1984 and Michale Eisner’s tenure as CEO, that the company expanded to bulk up its TV output. They bought a studio in Australia (owned by Hanna-Barbera until then), and outsourced a lot of the work to the Tokyo Movie Shinsha studio in Japan. “DuckTales” (1987 – 1990) whose characters and storylines were partly based not the “Donald Duck” comic books by Carl Barks, was their first success (see “The Golden Goose – Part I” (1990) episode (22min) by Rick Leon). It was followed by several other series, many of which (although not all) were based on existing characters or feature films (i.e: “Chip ‘n Dale: Rescue Rangers” (1989 – 1990), “TaleSpin” (1990 – 1991), “The New Adventures of Winnie the Pooh” (1988 – 1991) etc.). The company continues to produce children TV series and has expanded its style and use of techniques over the years. Recent successes include “Gravity Falls” (2012 – 2016), “Phineas & Ferb” (2007 – 2015), “Kim Possible” (2002 – 2007), and a reboot of “Ducktales” (2017 – 2021).

TV Animation for Adults

Matt Groening’s (born 1954) “The Simpsons” (first broadcasted in 1989 and still in production today), is the longest-running animated television series. While other series had aimed at an adult audience before (see “The Flintstones” above), few had done so successfully and the primetime time slot was still seldom occupied by animated shows. The Fox Network was launched in 1986 and the chance it took in airing edgy content such as “The Simpsons” would turn it into a major network and lead to a new and lasting trend of adult animated series.

“Characters on “The Simpsons” first found their voices (and early sense of humor) in shorts that accompanied Fox’s “The Tracey Ullman Show” from 1987 to 1989. Matt Groening, originally planned to adapt his popular “Life in Hell” comic strip into bumpers (brief announcements placed between a pause in the program and its commercial break, and vice versa) for the show, but balked upon discovering he would have to give up the rights to his creation. Thus the Simpson family was born. It all started on April 19, 1987, with “Good Night” — 47 more shorts were created over the next two years. They’re clearly personal — Groening named and modeled the characters after his own family — and remarkably crude. As Groening told the BBC, he submitted hand-drawn sketches to his animation team and was stunned when they just traced over what he gave them. However, even in “Good Night,” (1987) (2 min) (see below) you can see the roots of the Simpsons’ quirky subversion of the modern American TV family. We watch as Homer and Marge try to put their kids to bed, but instead of comforting the kids, they traumatize them; all three children wind up shivering in Marge and Homer’s bed. That idea that a well-meaning action can go horribly awry became a foundation of “Simpsons” humor.” (from ‘The Simpsons’ at 30: Six Era-Defining Episodes “ by Brian Tallerico)

Christopher Cook, a British cultural historian, has called The Simpsons “one of the very first postmodern TV shows developed for mainstream US TV. Someone once defined postmodernism as an ‘aesthetic of quotations’, in other words it collages material from pre-existing works in unlikely ways. And the ‘glue’ that holds the assemblage together is irony, knowing where the references come from and how they have been replaced. I see a lot of that on The Simpsons.” (from “How The Simpsons changed TV” by Stephen Dowling)

The show’s success heralded a new era of adult animated shows: Just from a timeline perspective, it makes sense that “The Simpsons” would be the predecessor to the Fox animation block and “Adult Swim”, but the connection runs deeper than that. Because “The Simpsons” established an audience for adult-focused animation, more controversial shows such as “South Park” (1997 premiere) and “Family Guy” (1999 premiere) were given a shot. Moving into more modern examples, the success of the central family relationship in “The Simpsons” — a nuclear, working class family that drifts between heartfelt moments and slapstick antics — allowed for your favorite shows to play with the formula. Whether you’re looking at “Bob’s Burgers’” (2011 premiere) sweetness or the disturbing dynamic of “Rick and Morty” (2013 premiere), they’re different incarnations of the same wildly successful, family-centric premise. (…) [Over the years, the show has recruited] some amazing guest animators. Everyone from “Ren & Stimpy’s” John Kricfalusi and the iconic Guillermo del Toro to the elusive Banksy and the Oscar-nominated French director and animator Sylvain Chomet has animated for the show. Additionally, the series has acted as a sort of launching pad for other animated sitcoms, such as Fox’s “Bob’s Burgers” and “Rick and Morty”. (from “10 Ways ‘The Simpsons’ Changed The World” by Kayla Cobb)

Music-videos

The 1980s saw the emergence of a novel format perfectly suited for animation experimentation: the music-video. MTV was launched in 1981, and while it’s focus has changed over the years it had a strong connection to animated content early on – both as the primary broadcast of music-videos and with the development of original animated series aimed at young adults (i.e:”Beavis-and-Butthead” (1993 – 1997) created by Mike Judge; “Daria” (1997 – 2002) created by Glenn Eichler and Susie Lewis Lynn). Most of these shows were produced in MTV’s own animation studio which opened in the late 1980s and closed in 2001. Independent animators – including Jan Švankmajer (see week 8), and Bill Plympton (see week 14) – were commissioned to create animated logos for the network (see compilation below) as well as standalone short films.

One of the first and most influential animated music videos was the one for “Take on Me” by the Norwegian band A-ha (1985) (see below) which features rotoscoped animation by Candace Reckinger and Michael Patterson – two recent CalArts graduates. The technique is used to blend comics panels with live-action footage:

In 1991, the video for Michael Jackson’s “Black or White” (directed by John Landis who has also directed the “Thriller” video) used a novel form of CGI morphing to fluidly shift between several live action close ups (see below – morphing starts at 3:40 min)

Animation – in all its format and techniques – continues to be very popular for music videos in every musical genres. Here are a few recent examples from Jay-Z, Radiohead, Daft Punk, Gorillaz, Kanye West, Wilco, REM, Home and Dry, Taylor Swift, Run the Jewels.

In recent years, interesting experiments with interactivity have come from animated music-videos, as in “The Johnny Cash Project” (2010) by Aaron Koblin and Chris Milk (see website below) : “A hand-drawn, animated, music video with each frame drawn by a different person. Participants are invited to create a drawing that is woven into a collective music-video-tribute to Johnny Cash. Set to his song “Ain’t No Grave,” the project was inspired Johnny’s central lyric “Ain’t no grave can hold my body down.” It represents Cash’s continued existence, even after his death, through his music and his fans. The work continues to grow and evolve as more people participate.

Japanese TV animation

“The earliest animation to air on [Japanese TV] was “Mogura no Aventure” (“Mole’s Adventure”). It was in color, used paper cut-outs, and was nine minutes long. Two years later in 1960, an experimental animated anthology called “Mittsu no Hanashi” (“Three Tales”) was created and aired by NHK (Japan’s public broadcast channel) as a special. Comprised of three ten-minute segments telling fantasy tales, it would make the journey to the United States the next year, where it was the first anime to air on American television.

In 1961, the anime “Otogi Manga Calendar” began regularly airing on Japanese TV. Each episode explored “what happened on this day in history,” sometimes supplementing its animation with historical photographs. The episodes were only three minutes long, but the series notched up an impressive 312 of them during its initial run. Three minutes, however, isn’t what usually comes to mind when we think of an anime episode. We think twenty-five minutes, give or take time for commercials. What was the first anime in the format we know and love today?

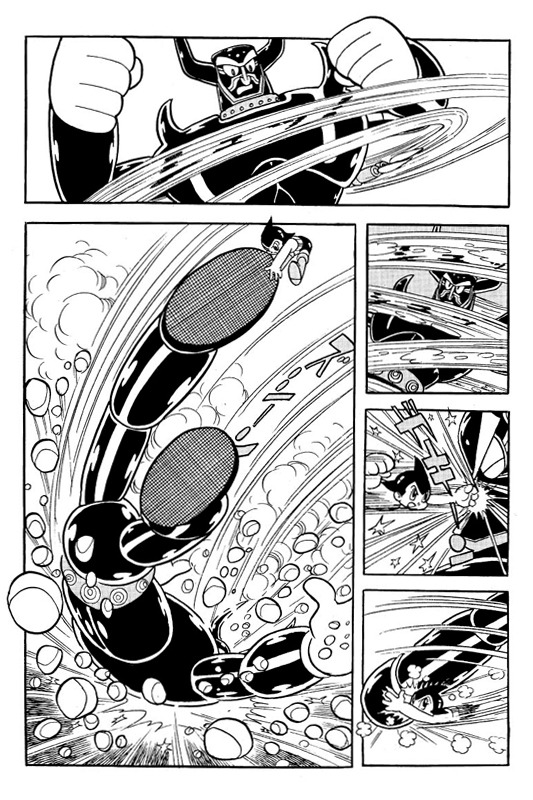

In 1963, Osamu Tezuka (1928 – 1989) and Mushi Pro [the studio headed by Tezuka] debuted the very first anime TV series we would recognize as such: “Tetsuwan Atom” (“Astro Boy”) (1963 – 1966) (see episode 1 (26 min) (dubbed) below). Based on one of Tezuka’s most popular manga, the show starred a robot boy who lived with humans and regularly battled crime, aliens, and other robots. Anime had never been tried on TV in a half-hour timeslot before due to cost and deadline concerns. How could such a time-intensive process ever be used to profitably air a show a week? Tezuka used what is called “limited animation”: techniques such as reducing the number of frames per second of film, re-using cels, and putting different parts of a character, like the head or arms, on different layers of cels so that only the part of the body moving needed to be animated in each scene. He also saved time by using his original manga panels as storyboards, eliminating much of the need to write and layout individual episodes. “Astro Boy” was a huge success with high ratings, merchandise galore, and syndication in dozens of countries (including the USA). (..) Many tropes we think of when we think “anime” today were codified by “Astro Boy” , including big eyes, robot battles, and stylized hair impossible to achieve in normal gravity. It was the coolest thing on TV and everyone loved it! …mostly. Its popularity surprised many of the more “serious” Japanese animators. Limited animation is comprised of literally cheap tricks, so how can it compare to the fluid animation and artistry of carefully crafted films? Can limited animation be art? This argument about limited animation versus fluid animation is another aspect of anime that continues today.

“Astro Boy” proved definitively that anime could be made for TV and be profitable. Tele-Cartoon Japan (TCJ, or Eiken post-1969) jumped on the bandwagon with Sennin “Buraku” (“Hermit Village”) in the fall of 1963. Based on a popular manga, the story was a risqué romantic comedy set in historical China and aired in a late-night spot. “Tetsujin 28-Go” (“Iron Man No. 28”), also from TCJ and about a boy and his giant robot, hit the air just a month later in October, though you may know it by its American name, “Gigantor”.

The next year in 1964, Tokyo Movie Shinsha (TMS) formed, and their first animated release was a TV series called “Big X”, based on another Tezuka manga. Over the years, TMS and its subsidiaries, including A Production, Shin-Ei Animation, and Telecom Animation Film, would frequently supplement their original productions with outsourced work for other companies, most notably Disney (see section above).

“Astro Boy’s” first year was done on a small budget from Fuji TV plus money from a candy sponsor, but the next year money came in from a surprising source: NBC in America, which was running an adaptation of the series to good ratings. This enabled better animation for later episodes of “Astro Boy”, but the bigger effect would be on an industry that had just discovered a new source of income. Animation studios trying to replicate the series’ domestic and international success began popping up left and right – and sometimes closing just as fast when they learned even limited animation still takes a lot of work, and not every story is as popular as one of Tezuka’s established manga properties.

NBC didn’t need an endless number of “Astro Boy” episodes, but they liked Tezuka. They asked him for a new show, specifying that this series had to be in color or else American audiences wouldn’t be interested. Cost? NBC would pay for the expense of converting [the] Mushi Pro [studio] to color. Tezuka agreed (free color!), and despite some friction between the creator and the American company (Tezuka kept trying to slip in death scenes and continuity; NBC kept trying to edit them out),“Jungle Emperor” (“Kimba the White Lion”) debuted in the fall of 1965, the very first color anime TV series and a popular success.

Not to be outdone, Toei Doga [studio] (see week 8 and week 13) put out the first “shojo” (targeted at girls between 6 and 15) and magical girl anime in 1966. Based on a manga by Mitsuteru Yokoyama, “Magical Girl” starred young witch princess Sally, who accidentally teleported to Earth and then stayed to have fun with her new friends. The first episodes were produced in black and white, but episodes 18 onward were made in color and the show had success in numerous other countries.

Tezuka left Mushi Pro in 1968 to found Tezuka Productions. Mushi Pro, facing budgetary difficulties and without its founder, closed in 1973. Several of its former animators founded studios of their own, to the point where for a while it seemed that the Venn diagram between studios founded in the ‘70s and studios founded by Mushi Pro staffers was a neat circle.

In the years after Tezuka left and prior to closing, Mushi Pro had been contracted to produce animation for film studio Zuiyo Eizo. In 1974, Zuiyo Eizo began producing animation itself, most notably “Alps no Shojo Heidi” (“Heidi, Girl of the Alps”) (1974) (see opening theme (1 min) below). Heidi was instantly popular, which might not surprise you if you recognize the names of its director, Isao Takahata, and layout director, Hayao Miyazaki.

Two Japanese cultural institutions made their appearance in 1979. Sunrise released “Mobile Suit Gundam”, in which giant robots were given a take grounded in science and politics. The show wasn’t actually too popular – until the toy company Bandai bought the merchandise rights and started releasing Gundam model kits (which inspired ” “Transformers” – see section above). Since then, over 70 “Gundam” series, specials, and movies have been made and hundreds of millions of action figures sold.

The 1980s are considered the “golden age” of anime and saw a huge explosion of genres and interest. Many factors contributed to this, including the introduction of VHS and children who were inspired by “Astro Boy” twenty years ago, growing up and becoming nostalgic for their favorite shows.

In 1986, Toei animated Akira Toriyama’s “Dragon Ball” (1986 – 1989) (see original opening theme – 2 min – below). The show proved incredibly popular, to put it lightly. If there’s a “shonen” (targeted at boys around ages 6 to 15) series you’ve enjoyed in the last 30 years featuring drawn-out battles and ever-increasing hero power-ups, its author probably watched “Dragon Ball” or its successor “Dragon Ball Z” (1989 – 1996) as a kid.

In 1995, Gainax released “Neon Genesis Evangelion” (1995 – 1996), a deconstruction of the giant-robot genre full of intriguing iconography, dark themes, and broken but likable characters. It immediately caught the attention of the anime world, and would have an influence on robot shows going forward that cannot be overstated. In addition to its takes on robot technology and the psychology of using teenagers as pilots, Evangelion’s two main heroines left huge marks on the anime world. Asuka and Rei respectively characterized what would be come to known as the popular “tsundere” and “moe” personality types. (Tsundere refers to a character who initially acts cold but warms up later, while moe is approximately a cute character you feel intense protective feelings for.) Asuka and Rei weren’t the first written in this mold, but the amount of merchandise sold featuring the girls was and is a juggernaut that still rakes in the yen today. Netflix acquired the exclusive rights to the series in 2019 (see the trailer (1 min) for the release on the streaming platform below).

The first anime based on a video game was “Super Mario Brothers: Peach-hime Kyuushutsu Daisakusen” (“Great Mission to Rescue Princess Peach”) in 1986, but the genre came into its own spectacularly and profitably with “Pokemon” in 1997. It’s still on the air and studios are still trying to replicate its international success.

Anime is recognized around the world as a reliable source of entertainment and art. Where early Japanese animators were inspired by the works of Disney, now Western shows like “Avatar: The Last Airbender” (2005 – 2008) and “Samurai Jack” (2001 – 2017) are taking their cues from Japan.” (from righstufanime.com)

Introduction to Long Paper Guidelines and Grading Rubric

Your long paper is due on week 15 (the thesis/outline is due on week 12, and the draft on week 13). Please review the guidelines and grading rubric here and start brainstorming possible topics.

ASSIGNMENT: Journal entry

Respond to your professor’s journal entry prompt (examples can be found on this page)