Mid-Century Shifts in American Design

In the immediate post-war period there were many cultural changes in society that are reflected in approaches to art and design. These changes are evident in animation as well. Fear of a communist threat in the USA and Canada led to blacklisting writers and artists in the film industry. Changes in consumer buying patterns led to an increase in animated advertising. We will look at all of these developments this week.

Jump to the different sections with the links below:

Overview of mid-century art & design / Background design evolution at Warner Bros. & Disney / Disney Strike / UPA Studio / The Blacklist / Storyboard Studio / Rise of animated advertising | Quiz 2 |Introduction to Extra-Credit Presentations (Optional) | Assignment

Overview of mid-century art & design

The post-war period was one of prosperity in the United States. It was also a period of cultural and social change which were reflected in the art and design of the period. Design in particular became more central to the aesthetics of the time. The style of mid-century modern embraced principles seen first in the International Style of architecture and the Bauhaus school of design that were seen in Europe in the 1920s and 30s. Functionality is emphasized, as is simplified, clean lines and abstract shapes. Colors are often bright and saturated.

Charles and Ray Eames

Charles (1907–1978) and Ray (1912–1988) Eames were American industrial designers who also worked in graphic design, art and in film. Their work is was influential in many fields during this period.

“Husband-and-wife design team Charles and Ray Eames were formative and among the most influential figures in American design of the mid-twentieth century. Born in St. Louis, Missouri, Charles Eames (1907–78) trained as an architect and worked early in his career for engineers, which evolved into a lifelong interest in mechanics and the complexities of how things worked. Bernice Alexandra (Ray) Kaiser Eames, (1912–88) born in Sacramento, California, had an interest in the abstract, and in the 1930s studied painting under Hans Hofmann in New York. Together, the Eameses embraced the concept of modern design as an agent of social change, creating designs for the overlapping needs of client, society, and designer and developing products that would serve all three. Their interests and visions would blend seamlessly into the creation of influential, lasting designs.” (from “ Ray Kaiser Eames” Cooper Hewitt https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/people/18050087/bio#ch retrieved June 2021)

The Information Machine (1957) was the first animated film created by the Eames for IBM’s Pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World Fair.

Mary Blair

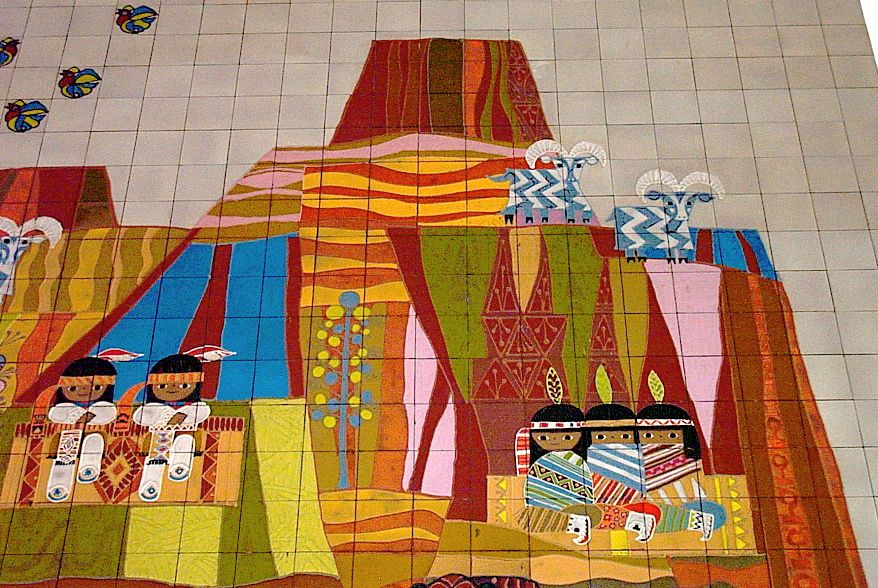

Mary Blair (1911-1978) was an American animator who is well known for the concept art she created for the Disney Studios. Blair illustrated a number of children’s books and worked on the design of Disneyland’s attraction “It’s a Small World” and the Mexican Pavilion at Epcot Center, and designed a mosaic for Disney’s Contemporary resort.

Blair started working in animation in the 30s for MGM, then for Ub Iwerks. She worked for Disney in 1940, leaving briefly in 1941. Blair accompanied Disney on a tour of South American countries. Blair worked on the partially animated features Song of the South (1946) and So Dear to My Heart (1948). She worked on color design and concept art for Cinderella (1950), Alice in Wonderland (1951), and Peter Pan (1953).

“An imaginative color stylist and designer, Mary Blair helped introduce modern art to Walt Disney and his Studio, and, for nearly 30 years, he touted her inspirational work for his films and theme parks alike. Animator Marc Davis, who put Mary’s exciting use of color on par with Matisse, recalled, “She brought modern art to Walt in a way that no one else did. He was so excited about her work.” Animator Frank Thomas added” (from “Mary Blair” Walt Disney Archives https://d23.com/walt-disney-legend/mary-blair/ Retrieved June 2021)

“Remember that heartbreaking scene from Disney’s 1941 feature “Dumbo” when the little elephant visits his mom in jail and she reaches her trunk through the bars to caress her baby? How about Disney’s 1950 film “Cinderella,” when birds and mice dance through the air as they help Cinderella sew a gown to wear to the prince’s ball? Or recall the moment in Disney’s 1953 film “Peter Pan” when the children soar with Peter Pan around the top of London’s Big Ben?

These were all ideas that Disney artist Mary Blair helped dream up. In a large company team, for which Disney himself took much of the glory, she was one of the most iconic artists. Then she left the studio in the 1950s to work in advertising and illustration, including producing Golden Books like her 1951 children’s picture book masterpiece “I Can Fly.” Then Disney himself recruited her back as the lead stylist behind Disneyland’s famous “It’s a Small World” boat ride.” (from Cook, Greg “Modernist Cute: Mary Blair’s Art For ‘Dumbo,’ Golden Books, ‘It’s A Small World’” WBUR.org https://www.wbur.org/artery/2016/02/15/mary-blair Retrieved June 2021)

Background design evolution at Warner Bros. & Disney

Warner Bros.

At Warner Bros., a modern design aesthetic appeared first in approaches to backgrounds and layouts. Chuck Jones encouraged his team to experiment. The backgrounds were incorporated into the plots. John McGrew (1910-1999) created the abstract graphic backgrounds for The Aristo-cat (1943). Bernyce Polifyka (1913-1990) designed the layouts and Eugene Fleury (1913-1894) painted the boldly patterned backgrounds for Wackiki Wabbit (1943). This team worked together on a number of other animations directed by Jones..

Maurice Noble (1911-2001) began to work for Warner Bros. in 1952.. He had been a background artist at Disney, working on the “Silly Symphonies” series and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. He left after the Disney strike, working for a time for the Army Signal Corps. He continued to collaborate with Jones at Warner BBros. for many years.

“The Jones unit worked with many of Warners characters: Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Road Runner & Coyote. Noble’s wide-open desert landscapes gave the Road Runner cartoons their characteristic spaciousness. The cartoons Noble designed at Warners include What’s Opera, Doc? (1957), a Bugs Bunny parody of Wagner’s Ring Cycle that has been inducted into the National Film Registry. Noble’s futuristic settings enhance Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century (1953). Other cartoons included the Academy Award nominees From A to Z-Z-Z-Z (1954), High Note (1960), Beep Prepared (1961), Nelly’s Folly (1961), and Now Hear This (1962).”(from “Maurice Noble”. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maurice_Noble Retrieved July 2021)

Disney

Mary Blair’s work contributed to the look of many Disney projects. Disney never fully embraced the “modern art” style, but it was used in some of the studio’s short films. Pigs is Pigs (1954) had backgrounds by Eyvind Earle and Al Dempster that showed an inventive use of flattened backgrounds and a graphic style.

One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961) was the first Disney feature film to use xerography rather than inking.. Walt Pereguy was the color stylist on the film and he used this process to create bold areas of color inside of the black, photocopied lines.

“Xerox had begun developing a photocopying process before Word War II. By the 1950s, a commercial version was available for businesses, but it focused on paper, not film. Ub Iwerks (the co-creator, with Walt Disney, of Mickey Mouse) was impressed enough by what he saw to work with Xerox to adapt the technology for film, and the final process allowed animator drawings to be printed directly onto cels. This accomplished two things: one, it freed Disney from the need to hand ink each and every animated cel (the process which had significantly raised the costs of Alice in Wonderland and Sleeping Beauty, and the costs of releasing two versions of Lady and the Tramp) and it meant that instead of having to hand draw 99 little Dalmatian puppies, Disney could, for all intents and purposes, just photocopy them.

The resulting process did lead to some sloppiness: if you watch the Blu-Ray edition closely, and even not all that closely, you can still see the original pencil marks around some of those black lines. The lines, too, are far thicker than the delicate lines used in earlier Disney animated pictures, something that would not be improved until The Rescuers (1977), and often uneven. This might be the one Disney film you’re better off not seeing in Blu-Ray, is what I’m saying. It also reportedly led to one error: viewers who have counted all of the puppies in the final scene have claimed that it has about 150 puppies, not 99, probably thanks to the ease of photocopying the puppies. (I didn’t try to verify this.)

And since the xerography process could initially only reproduce black, not colored lines, animated characters from One Hundred and One Dalmatians through The Rescuers, and even most of the characters in The Rescuers and later films, were all outlined in black, in strong contrast to the colored outlines that Disney had used to such great effect in Fantasia and some of the Sleeping Beauty sequences. It also forced animators to move away from the more realistic animation used for the dogs in Lady and the Tramp (which did not have to be drawn with hard, black lines) to a more cartoonish look used for One Hundred and One Dalmatians and pretty much every animated animal in a Disney film until Beauty and the Beast in 1991.” (from Mess, Mari. “The Advent of Xerography: Disney’s One Hundred and One Dalmatians”. Tor.com. https://www.tor.com/2015/07/23/the-advent-of-xerography-disneys-one-hundred-and-one-dalmatians/ July 23, 2015.. Retrieved July 2021)

The “making of” for 101 Dalmatians below includes a section about the Xerox process (11:40 – 14:25) :

Disney Strike of 1941

The Disney strike of 1941 had a profound impact on the company, with much of the staff leaving the company, many fired by Disney. Some of them left to form UPA.

“Disney artists considered themselves the patricians of the industry, under Walt’s benevolent rule.

But anger over the long-promised profit sharing from Snow White, alienation over blunt maneuvers by Disney lawyer Gunther Lessing, and other conditions made the workers sympathetic to the call to unite.

The strike lasted for five weeks, forever tearing the social fabric of the studio.Walt felt personally betrayed when Art Babbitt, his highest-paid animator, resigned as president of the Disney company union to join the Guild. Three days after Disney brazenly fired Babbitt, the Disney strike began on May 29, 1941.

FDR sent a Federal mediator, who found in the Guild’s favor on every issue. Walt left on a Latin American tour to ease tensions.

Fearing the loss of government contracts and the recall of bank loans, Disney signed and has been a union shop ever since.” (from “The Disney Strike, 1941” The Animation Guild https://animationguild.org/about-the-guild/disney-strike-1941/ Retrieved June 2021)

UPA Studio

“United Productions of America (UPA) was an animation studio based in Hollywood, California from 1943–2000 that produced its most famous and influential works from 1943–60. In 1941, a labor strike at Walt Disney Animation Studios left a group of trained artists seeking other employment—of these Disney-trained animators, Stephen Bosustow, David Hilberman, and Zachary Schwartz soon founded UPA. The United States’ entry into World War II created a need for war-related propaganda and training films, and UPA quickly began producing animated industrial shorts that experimented with contemporary graphics. The studio’s left-leaning politics made them particularly suitable to FDR’s democratic administration, and they received regular government work during the war. In 1948, UPA secured a deal with Columbia Pictures’ Screen Gems division and produced a number of very successful and highly influential animated shorts, many of which were nominated for Academy Awards and three of which won Oscars for best animated short. Rapid turnover from the studio and high praise from the press meant that UPA’s style came to define 1950s animation in studios across the country—The Museum of Modern Art even featured the studio’s work in a 1955 exhibition entitled “UPA: Form in the Animated Cartoon.”

The studio’s contemporary aesthetic was distinguished by an embrace of modern graphic design rather than traditional animation. As a result, UPA’s films featured simplified forms with hard edges and minimal detail—traditional perspective was discarded for landscapes composed of bare geometry, regular patterns, or even a single flat color plane. The flat animation style created a sense of infinite depth and opportunity, placing characters in imaginative and surreal environmental surrounds. UPA also pioneered the use of limited animation—rather than creating unique details for every frame, UPA designers reused common parts between frames, creating a style that was more stylized and abstract and that also enabled fast production. In addition to style, the content of UPA films challenged what animation could be, presenting shorts that focused on drama rather than humor. By the late 1950s, the demand for animated shorts to air before feature films in movie houses had fallen off. Columbia shut down the animation house in 1959, selling UPA in 1960 to Henry Saperstein, who turned it into a television studio.” (from “United Productions of America (UPA)” Cooper Hewitt https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/people/1108826279/bio)

Hell Bent for Election (1944) was one of the first UPA animations, created by free-lancers. It was directed by Chuck Jones and sponsored by the United Auto Workers. It is a campaign film, designed to encourage citizens to register and vote for Franklin D. Roosevelt.

John Hubley

John Hubley (1914-1977) was an American animator, director, art director and producer. He worked as a background and layout artist on many of the Disney features in the 30s and 40s. Like many others, he left Disney during the strike of 1941, working for Screen Gems and the Army’s First Motion Picture Unit before he joined UPA.

He developed the Mr. Magoo character for UPA and directed the first animation with the character.

Gerald McBoing Boing (1950) is based on a story by Dr. Seuss, directed by Robert Cannon and produced by John Hubley. It tells the story of a little boy who speaks with sound effects rather than language. It won the Academy Award for Best Animated Short in 1950.

Rooty Tooty Toot (1951) tells the story of the song Frankie and Johnny. Hubley co-wrote, directed and produced the film, which was animated by Art Babbit, Pat Matthews, Bob Mc Donald and Grim Natwick.

Hubley was forced to leave UPA in 1952 when he would not testify before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, naming names.

The Blacklist

During the 1940s and 50s, many Hollywood studios would not hire people in the industry that were seen as having sympathies with Communist ideology. This affected writers, actors, directors; basically everyone who potentially would be working in the entertainment industry.

“The culture war anti-communists waged against those identified as subversive and politically impure reverberated across broad swaths of media, encompassing the liberal and literary left (poetry, novels, children’s literature, and non-fiction), news (print and broadcast), and mass-mediated popular culture (animation, film, radio, and comics). Conservatives attacked poetry in the 1950s, claiming that experiments with form (and thus challenges to tradition and convention) were a communist plot against American culture. Literary scholars have abundantly documented the impact of the Red Scare on African American literature, since anti-communists believed that cultural production on the part of black people could only be the work of outside (read: white) agitators. As literary critic William J. Maxwell put it, the FBI waged a “fifty-year crusade to bully and savor African American writing, always presumed to be a type of communist sophistry.” The anti-communist crusade, which eventually expanded to include all American popular culture, stifled creativity across media industries, including those from which television might have drawn for inspiration and innovation.” (from Stabile, Carol A.. “How the Communist Blacklist Shaped the Entertainment Industry As We Know It” Portside https://portside.org/2018-10-12/how-communist-blacklist-shaped-entertainment-industry-we-know-it October 12, 2018 Retrieved July 2021)

Storyboard Studios / Hubley Studios

“After John Hubley was blacklisted by HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee) for not testifying before the committee, he had to leave his position at United Productions of America (UPA) in 1952 and as a result founded his own independent animation studio, Storyboard Studios, in the following year. At the beginning, he worked on television commercials but after he moved his studio from Los Angeles to New York City in 1956 and started collaborating with his second wife Faith, the company turned to making and producing independent short animated films. Together they produced one independent animation a year, 22 films in total. Seven of these were nominated for Academy Awards, and three, Moonbird (1959), The Hole (1962), Tijuana Brass Double Feature (1965), won the Oscar.

The Hubleys still produced commercials for Easy Pop and Maypo, as well as create animated shorts for Sesame Street. One could notice a number of characteristic traits in the films produced by Storyboard Studios. Story-wise, the Hubleys often focused on human nature in their animations, for instance in Moonbird (1959), Cockaboody (1974), and Everybody Rides the Carousel (1975).

Secondly, they also touched upon social issues in their films, for example warning against nuclear destruction in The Hole (1962), depicting the absurdity of war in The Hat (1964), questioning urban development in Urbanissimo (1966) and overpopulation in Eggs (1970), and fighting for children’s rights in Step by Step (1979). In terms of their style, many scholars and animators point out to Hubley’s distinguish style, particularly their dependence on animal characters which could metamorphose into anything, and freedom in drawing and coloring, with much of the coloring not staying within the lines.

Moreover, Mary Corliss, Assistant Curator at MoMA, argues that Storyboard’s films represent impressionistic style influenced by modern painters such as Picasso, Matisse, Klee, and Miró. Hubleys’ films also distinguish themselves by their innovative use of soundtrack. The Hubleys often improvised with soundtrack (they were the first artists to use real children’s voices instead of actors’ voices for children’s characters), and used jazz musical accompaniment from many leading musicians, such as Benny Carter, Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, and Quincy Jones.

After John’s death in 1977, Storyboard Studios, renamed Hubley Studios, continued to operate under the supervision of John’s wife, Faith, and their daughter Emily. The studio produced an independent animation each year, continuing with the themes and style developed during John Hubley’s life, but also representing Faith’s individual style. In 2000, the studio produced its final film Our Spirited Earth. The next year, Faith Hubley died and the Hubley Studio closed its doors.” (from “Storyboard Studios / Hubley Studios” Rarebit Early Animation Wiki http://rarebit.org/?studio=storyboard-studioshubley-studios Retrieved July 2021)

“At this point, John had been burned three times by commercial animation: during the Disney strike, at UPA, and by Finian’s Rainbow. Faith had never had anything but distrust of commercial projects to begin with. So as a condition of their marriage, they made a pact: They would make one serious film a year, for themselves, and do whatever they had to do to support it. Many people make this kind of one-for-them-one-for-me promise at the beginning of their careers; almost no one keeps it. John had been working in animation for nearly 20 years when he decided it was time for personal projects—and he and Faith kept their bargain, producing innovative, avant-garde films at a breakneck pace. John continued to work in commercials, and Faith worked in various parts of the film industry, including as a script supervisor on 12 Angry Men, but the goal was to support their own work. Here’s how John described the importance of this bargain to Ford:

…if you believe in this media as an art, and you believe yourself to be an artist, and you want to make films as an artist, you have to go ahead and do it; you have to make what you want to make, have control over it, and make it on your terms. The old struggle of art versus commerce and whether the artist can control creativity or be told what to do by the money people is one that we realize every artist is up against. Faith and I decided that we would separate the two functions and never let the necessity of earning a living interfere with the production of one film a year. In other words, make the living doing other things and always keep one film a year where you don’t have to worry about economics. (Well, you do worry about economics, because you’re pouring money into it and you can’t expect to get it back.) But it’s very important to do it, because it feeds your whole creative life.” (from Dessem, Matthes. “The Magnificent Hubleys” The Dissolve https://thedissolve.com/features/movie-of-the-week/734-the-magnificent-hubleys/ Retrieved July 2021)

Moonbird (1959) was produced by Faith and John Hubley, using the voice of one of their children.. It tells a story of 2 boys sneaking out and trying to catch a moonbird. Robert Cannon and Ed Smith animated the film.. It won the Academy Award for Best Animated Short.

Rise of animated advertising

The 50s saw an emphasis on the importance of finding new ways to sell products. In the US there was a post-war boom and boradcast television had become a dominant media. Designers were often key to this effort to find new ways to appeal to markets. Often a “modern art” style or look was used in these efforts, characterized by simple shapes, abstraction and bold use of color. Animated characters eventually developed during this period to represent brands, such as Tony the Tiger. A number of studios focussed on this effort.

UPA

“Throughout the 1950’s, television commercials were an important part of the UPA cartoon studio’s output. In fact, it’s widely believed that commercial work kept the company afloat, as their Columbia-released shorts often went over budget. Spots were produced at the main studio in Burbank, as well as the New York studio. ” (from “UPA Advertising” Cartoon Brew https://cartoonresearch.com/index.php/upa-advertising/ April 12, 2014 Retrieved July 2021)

Here is an ad for Triscuits produced by UPA in the 50s.

Playhouse Pictures

Playhouse Pictures was a studio in Los Angeles that created a lot of animated advertising.. It was founded in 1952 by Adrian Woolery (1909-1982), who had worked at Disney before the strike and at UPA.

This commercial for IBM was produced by Playhouse Pictures in 1961. It was designed by Saul Bass.

John Sutherland Productions

John Sutherland (1910-2001) started John Sutherland Productions, which produced many industrial films, propaganda films, and advertising. Sutherland was also a former Disney employee. Many of the films from his studio were sponsored by American corporations and extolled the American way of life. He also made a series of anti-communist propaganda films for Harding College..

A is for Atom (1952) was sponsored by General Electric. It defines an atom, explains nuclear energy and is an attempt to de-mystify it by showing peaceful uses of atomic power.

Sutherland’s studio made a series of animations for Harding College that focussed on a conservative political agenda that included the benefits of capitalism and problems with government intervention in corporate culture, including Make Mine Freedom (1948). These were funded by the Alfred. P. Sloan Foundation.

Quiz 2

Please take the second multiple choice quiz on Blackboard.

Introduction to Extra-Credit Presentations (Optional)

Review the guidelines here.

ASSIGNMENT: Journal Entry

Respond to the journal entry prompt(s) on this page.