Bathers, Paul Cézanne, 1874- 75

Podcast by Egile Rad

Podcast Transcription:

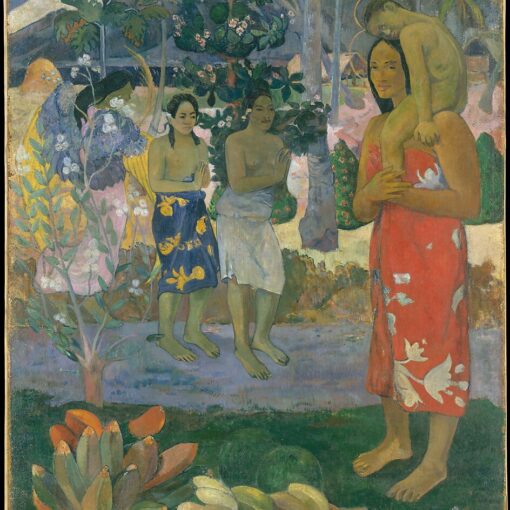

When approaching works in galleries, most of us follow similar patterns of analysis. We are

attracted to familiar shapes and palettes and recognizable settings. But what if there are

paintings that lure us in, much like some sort of flytrap, appearing familiar with clear

imagery, but upon closer look, aren’t really what they seem to be. Paul Cézanne’s painting,

Bathers, 1874 through 1875 is just that. Set somewhere in the French Provence, a region full

of rivers and coastal beauty, as well as Cézanne’s home turf, is not only a challenge to the

then dominant academic tradition of realistic figure depictions, but also a monumental

impressionist work that would reshape modern art.

At first glance, the scene appears deceptively simple: figures by a river, a timeless subject

that artists had painted for centuries. But the interpretation that Cézanne depicts disrupts

our expectations, creating a visual tension that forces us to reconsider how we look at the

human form. The six feminine figures, positioned by the flowing river, resist the classical

ideals of beauty and grace. Instead, they stand with an almost architectural stiffness, their

bodies reduced to simplified shapes that hover between real representation and abstraction.

This departure from tradition becomes even more pronounced when compared to his

contemporaries. While artists like Renoir and Degas made their own, naturalistic bather

scenes, Cézanne’s approach deliberately challenged the traditional bather motif – a subject

that, since the Renaissance, had been used to represent the ideals of female beauty.

In the version that Cézanne presents, the bathers’ androgynous form stems from a deeper

personal context. Art historians often recount how the artist, intensely uncomfortable with

female models, would flee his studio when they arrived for painting sessions. His notorious

unease with the female form manifests clearly in his work, creating this uncanny effect

where the figures appear both human and somehow as another form completely. Even

looking at their faces, we notice that they are barely detailed and represented mainly

through shadows, denying us the comfort of getting to know their individual identities.

He achieves this by a variety of technical choices that intensify this sense of awkwardness.

Primarily utilizing a singular, relatively thin flathead brush with varied strokes, he creates

thick, irregular textures throughout the canvas. The brushwork doesn’t try to hide itself –

instead, it becomes an essential element of the composition, and each stroke is visible and

purposeful. The color palette further transforms the scene. Instead of the warm, inviting

tones typically associated with figures in nature, Cézanne opts for a cold palette where

blues and greens dominate. This creates what could be described as a ‘scene of nature’

rather than an interaction of a traditional figure study and some sort of surrounding

environment; nature completely dominates the image. The color interaction between these

cool tones helps establish the painting’s unique atmosphere while contributing to the

figures’ ethereal being; with them blending in, yet in their sturdy form, establishing their

presence.

When looking at the composition as a whole, we are almost transported directly into the

scene. The moment depicted exists as a paradox, evoking feelings of both the immediate

happening and timelessness; as if some imaginary situation happened to be suspended in

time and put into one’s memory. Cézanne’s Bathers are monumental, in that its visual

language is able to transfigure reality through its distinct choices of depiction.

What makes this painting particularly revolutionary is how it bridges different artistic

movements. While rooted in Impressionism through its attention to light and atmosphere, it

points forward to Cubism through its simplified forms and geometric tendencies. We may

even observe that the awkwardness of the figures isn’t necessarily a flaw but a choice that

helps establish what would become a new visual language in modern art. Cézanne wasn’t

showing us his limitations as an artist – he was showing us the future.

These stiff, simplified figures, with their geometric forms and ambiguous features, become

essential phrases in the vocabulary of modern art. Through recontextualizing the human

figure, Cézanne achieved something profound: he showed us that beauty in art doesn’t lie in

perfection, but in our interpretations of the world and how we see it.

Reference List:

Danchev, Alex. Cézanne: A Life. Pantheon Books, 2012.

Reff, Theodore, and Innis Howe Shoemaker. Paul Cézanne: Two Sketchbooks. Philadelphia

Museum of Art, 1989.

Krumrine, Mary Louise. Paul Cézanne: The Bathers. Thames & Hudson, 1990.